Advanced Checklists

This tutorial describes a detailed workflow using Symbiota tools in the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria for compiling checklists based on specimen records available in the Consortium as well as records published in the literature.

For a general tutorial on ho to create checklists in Symbiota refer to the Symbiota Help Documentation on Checklists. There is also a beginner’s tutorial available here.

An example checklist was recently published for the country of Ecuador: Lichen-forming, Lichenicolous and Allied Fungi of Ecuador. An example how to create checklists in SEINet was recently published in Vol. 17 of Canotia by by Mackenzie E. Bell and Leslie R. Landrum: Making Checklists with the SEINet Database/Symbiota Portals.

Building checklists and managing checklist data using the Consortium provides an efficient and dynamic option to deal with large species lists from megadiverse countries, especially when dealing with poorly known groups, where the taxonomy frequently changes.

For a more detailed discussion of using the Symbiota tools, please review our publication:

Yánez-Ayabaca et al. (2023) Towards a dynamic checklist of lichen-forming, lichenicolous and allied fungi of Ecuador. The Lichenologist 55(5):203-222 [open access].

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Table Of Contents

- ‘Hierarchical’ vs. ‘Non-Hierarchical’ Checklists

- Uploading Existing Lists

- Voucher Tool

- Type Specimens

- Literature

- Taxonomy Cleaning

- Assign Categories

- Setting up the Header

- Version History & Downloads

- Publish the Checklist

_______________________________________________________________________________________

1. ‘Hierarchical’ vs. ‘Non-Hierarchical’ Checklists

Before you get started, it is a good idea to decide which kind of list you are planning to build.

Geographic/Geopolitical Hierarchies

Checklists built with Symbiota can be simple or they can be hierarchical. Thus, for a large country with many different provinces, it may make sense to build individual checklists for each province first, and then include these as children checklists for the country. The parent checklist will automatically inherit taxa included in any of the child checklists. Thus, you can build a checklist for Mexico, by first creating separate checklists for each state (Baja California, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, etc.) and then add these as children to its parent the national checklist for Mexico.

There are also some disadvantages to be considered when creating hierarchical lists:

(1) Hierarchical lists add complexity – each change made to any of the children checklists will be reflected in the parent. Managing a version history of checklists (see below) thus becomes more challenging, especially when dealing with a large country with many provinces and thus one principle list with multiple child checklists.

(2) Detailed information entered for a specific taxon may be different for a child checklist vs. its parent. Generally, information from the child checklist also appears in its parent – unless different information is entered there. Only if information has been entered for the parent it then supersedes information entered for the child.

An example: a species might be rare in one state (or province), but common in most of the country. To emphasize this difference, one would have to include a comment that the species is rare in that particular state, but also add a comment to the national checklist that the species is generally quite common throughout most states of the country.

Again this means: for large countries with many states (or provinces) maintaining separate hierarchical checklists adds a level of complexity and thus, higher maintenance of these checklists overall.

It is also possible, to use a mixed approach – building an general checklists of all species reported from a country, plus a few additional checklists only for the states/provinces that are best known, the ones having received the most attention.

Thus, in Mexico, for example, the northwestern states of Sonora, Baja California, and Baja California Sur have been reasonably well investigated as a result of the Lichen Inventory for the Sonoran Region, whereas only few species records are known from some of the other states in Mexico.

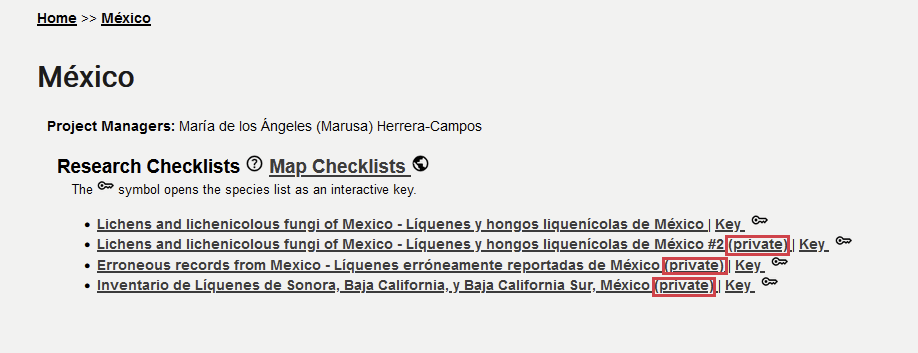

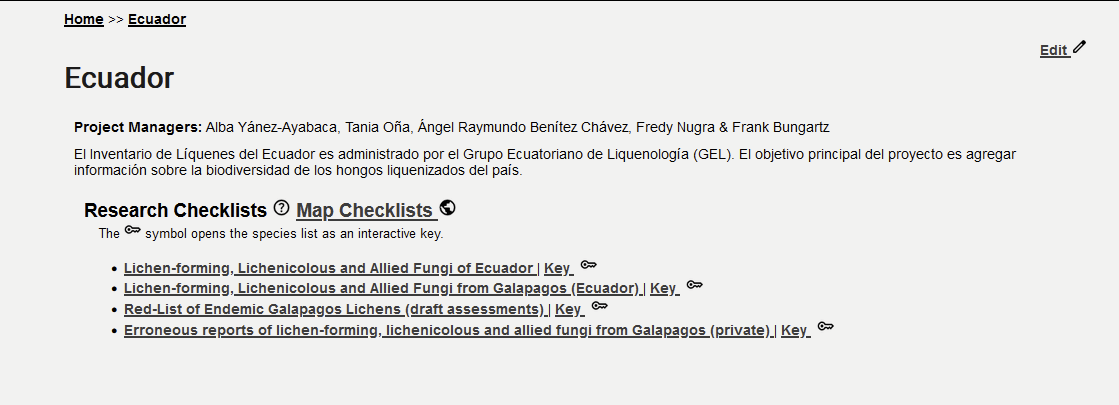

The Checklists of Ecuador as an example for hierarchical checklists:

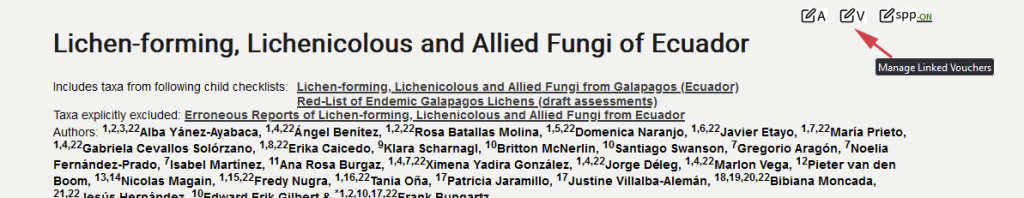

Four lists are available – (1) the main list for the Country of Ecuador, (2) a list for the Province of Galapagos, (3) a Red-List with draft assessments of species endemic to the Galapagos, and (4) a list of species erroneously reported from the Galapagos.

The main list of the country is configured as the parent of the Galapagos Checklist. The Galapagos Red-List is a child of the Galapagos Checklist and it is configured as a ‘rare, threatened and protected species list‘ [see below]. The list of Species erroneously reported from the Galapagos is a ‘species exclusion list‘, thus not feeding its records into the parent [also see below].

Hierarchical checklists are useful to distinguish lichen biota across geopolitical/geographic regions. But there are also two additional categories of child checklists:

‘Rare, Threatened & Protected Species Checklist’ ‒ this category is set up to include species from a region (country, state, etc.) that are considered rare and potentially threatened. Building such a checklist can be used to hide locality data for specimens vouchers from public view. Even though this checklists feeds data into the parent, vouchers included in this list will not be displayed on a map. These occurrence records remain hidden from the public and are accessible only with user rights that allow reviewing rare species occurrences. An example is the ‘Red-List of Endemic Galapagos Lichens (however: currently most records in this list are not hidden, because this is a list of draft assessments)’.

and

‘Species Exclusion List’ ‒ this category is set up for building checklists of taxa that have erroneously been reported from a region (country, state, etc.); unlike any other child checklist, taxa from an ‘species exclusion list‘ will not be included in its parent. An example is the list of ‘Erroneous reports of lichen-forming, lichenicolous and allied fungi from Galapagos‘.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

2. Upload Existing Lists

Checklists can either be constructed by adding taxa manually, in batch, or using the Voucher Tool. Adding taxa (species, subspecies, varieties, forms) to build a checklist only taxa available in the Taxonomic Thesaurus can be added. Taxa not included must first be added to the thesaurus before they can then be added to a Checklist (contact the portal administrator, if a taxon is missing from the thesaurus).

When building checklists manually it is strongly recommended to first review whether a name is considered ‘accepted’ or a ‘synonym’. Per default, taxa are being displayed in a checklists how they were originally added to that list, i.e., the ‘original checklist‘.

Building a list from scratch it is possible to accidentally add two different names of the same species. By switching the display from ‘Original Checklist’ to ‘Central Thesaurus’ it is possible to review, whether accidentally different names of taxa have been added, which the thesaurus considers synonyms (see Taxonomy Cleaning below).

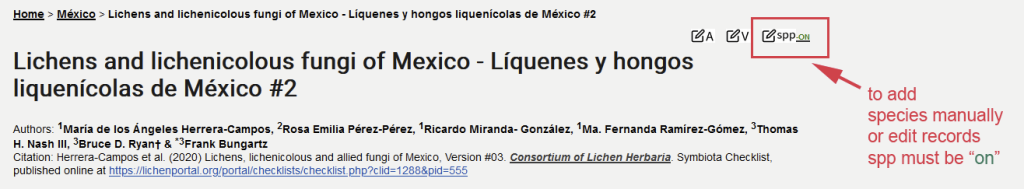

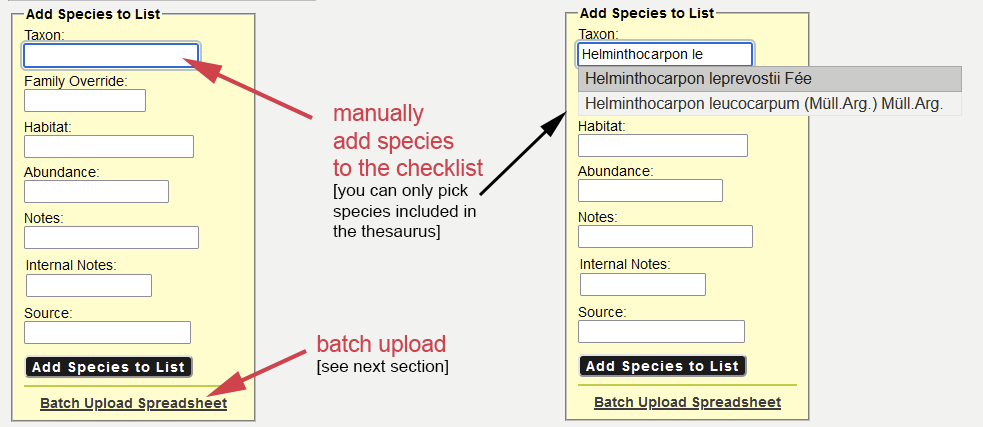

2.1. manually adding taxa

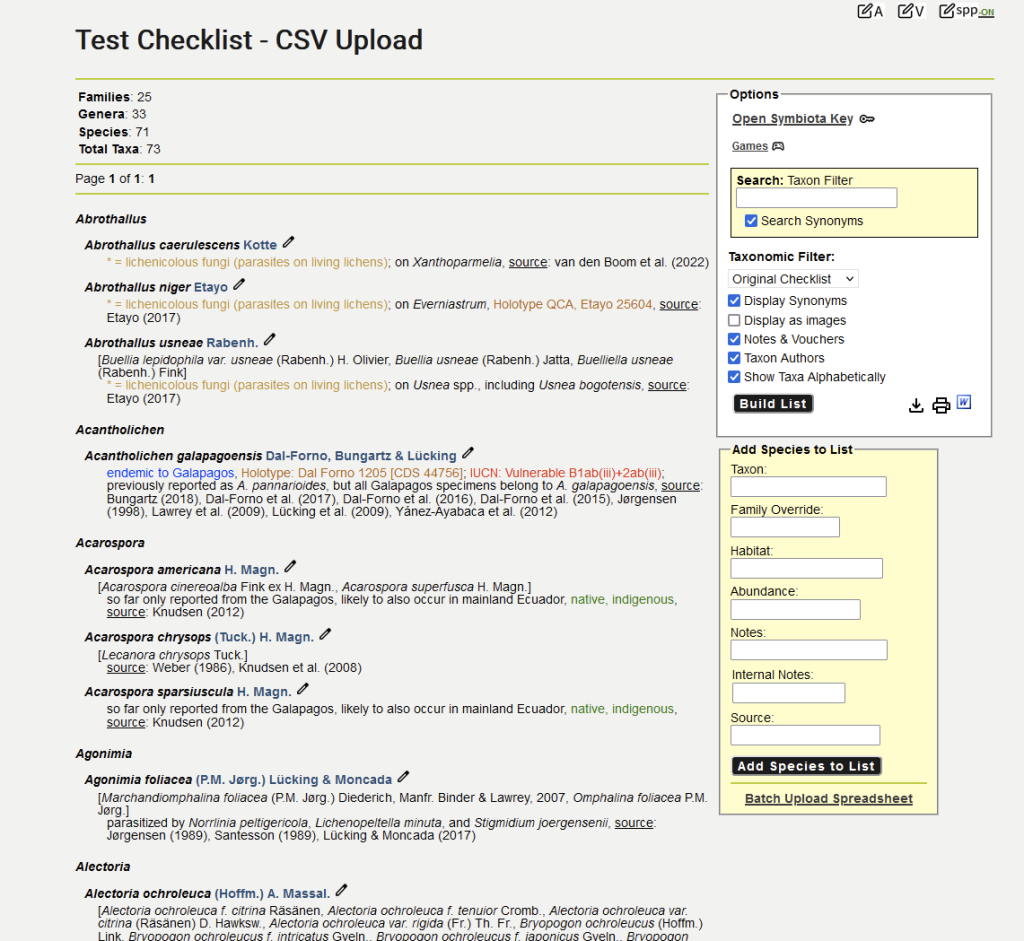

To manually add species records to your checklist, make sure ‘spp-on‘ is active (this option also needs to be enabled to manually edit any notes for each entry, discussed in detail later):

This opens a box where you can start typing species names to add them manually. For each species you can also additional information (family override, habitat, abundance, notes, internal notes, and source):

When you add individual species records to your checklist manually, it is important not to add duplicates of the same species using different names for the taxon.

For example, it is possible to accidentally add both Usnea longissima Ach. and Dolichousnea longissima (Ach.) Articus to the same checklist ‒ even though these are just different names for the exact same species, i.e., both taxa are based on the same type (= homotypic synonyms), simply reflecting different taxonomic opinions how the species should be named.

It is possible also to add names that the taxonomic thesaurus treats as heterotypic synonyms, i.e., taxa that are based on different types, but nevertheless considered synonyms. Taxonomic opinions change over time and authors of a checklist may disagree, thus this provides for an option not to follow the taxonomic concepts employed by the thesaurus.

For example, following the Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region, the taxonomic thesaurus lists Buellia glaziouana (Kremp.) Müll. Arg. as a synonym of Buellia mamillana (Tuck.) W.A. Weber. The two taxa are based on a different type and could be considered distinct species (again: this is a matter of opinion). In some instances, authors may deliberately disagree, treating two taxa as separate species, although the thesaurus considers them synonyms.

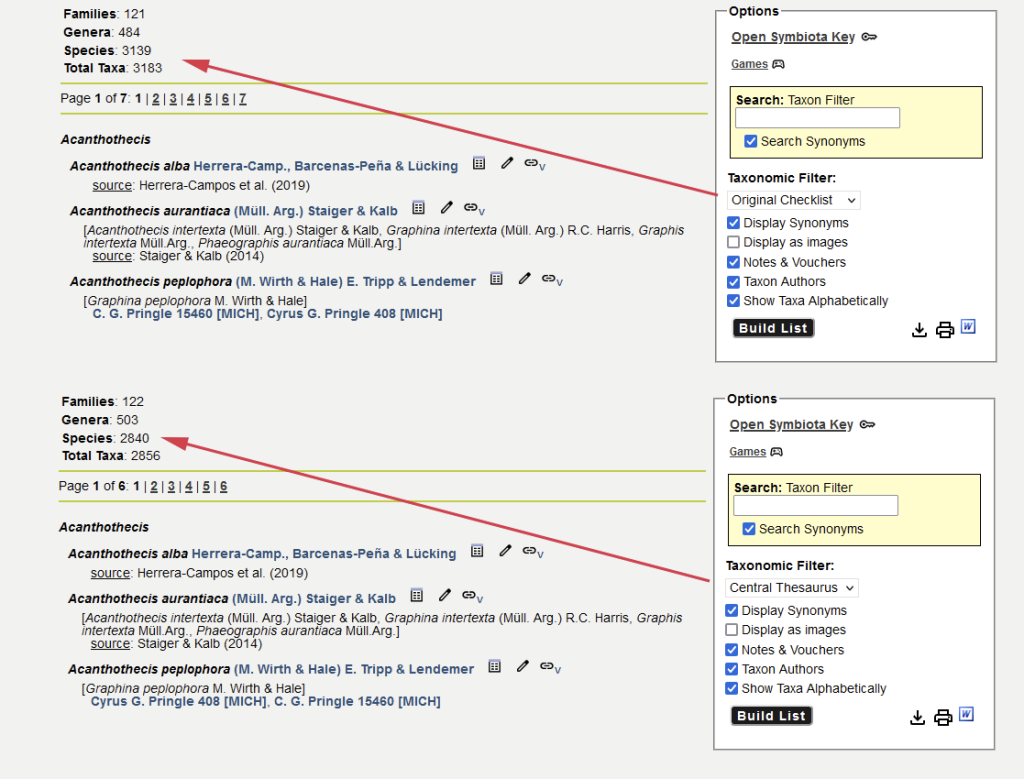

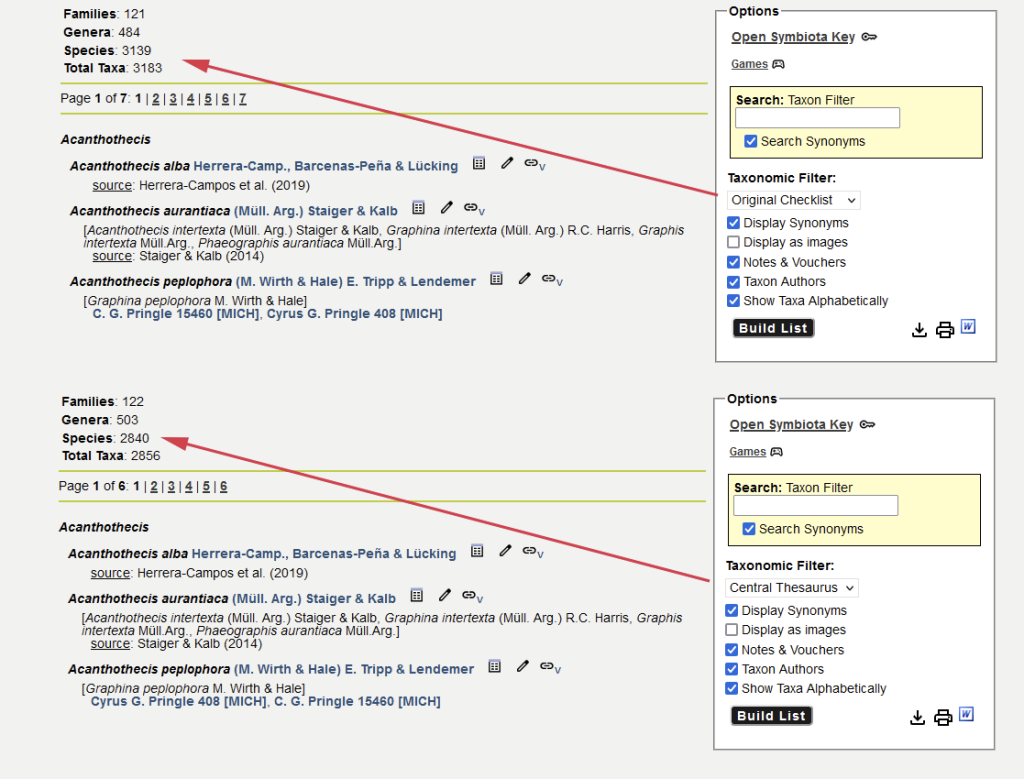

Changing the display option from ‘Original Checklist’ to ‘Central Thesaurus’ will then result in different statistics,. The ‘Original Checklist’ display will then display and different species count from the ‘Central Thesaurus’. While the ‘Central Thesaurus’ only counts the number of accepted names, the ‘Original Checklist’ counts all names that have been originally added to the list separately ‒ no matter whether these are synonyms or not.

Therefore, when adding synonyms as separate species not following theCentral Thesaurus, it is recommended to add a comment explaining the different taxonomic opinion. In most instances discrepancies arise, however, not because authors deliberately decided to disagree with the Central Thesaurus, but when false duplicates have been added accidentally. Then, it is necessary to download, compare and clean up the two lists [see Taxonomy Cleaning below].

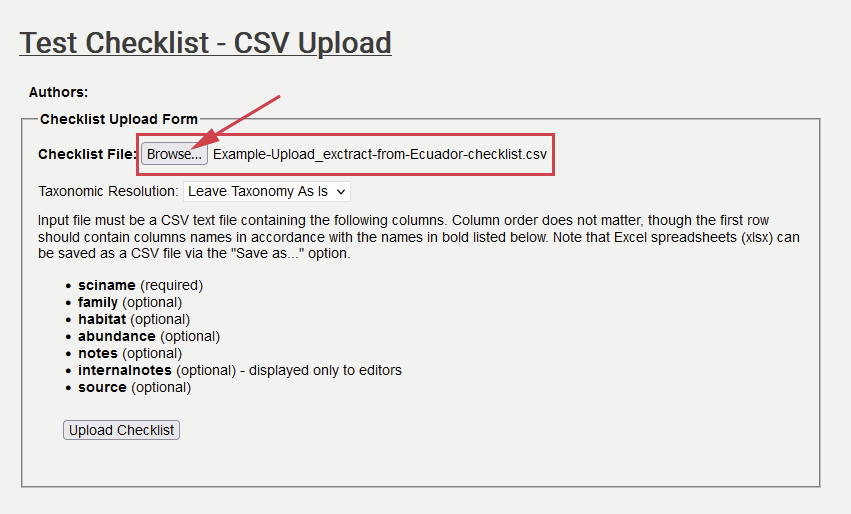

2.2. uploading checklists in batch

Instead of adding individual species manually one-by-one, it is possible also to upload an entire spreadsheet (= a list of species) in batch.

That spreadsheet may include only a single column, a simple list of the names to be added, or it can be a spreadsheet with one or several of the following fields:

sciname | family override | habitat | abundance | notes | internal notes | source

The only acceptable file format that can be uploaded is a text file with comma separated values [file extension: *.csv]. To manually compile such a file, you could use a text editor and separate columns by comma and enclose text that itself contains commas in quotation marks. However, most spreadsheet programs [e.g., Excel, LibreOffice CALC] allow you to save files directly as CSV. To assure that symbols are transcribed correctly, is recommended to save the CSV with UTF-8 encoding.

Below the list of fields that can be uploaded in batch [with the size and whether their title is displayed]:

sciname = The sciname is the ‘scientific name’ of a species without its author. Although a spreadsheet may include author names, during upload these are nevertheless ignored. The consequence: homonyms will not be distinguished during upload. So, if you upload a name like Caloplaca arizonica E.D. Rudolph [= a synomym of Caloplaca pellodella (Nyl.) Hasse] vs. Caloplaca arizonica H. Magn. [= a synomym of Gyalolechia epiphyta (Lynge) Vondrák] the two are not distinguished during upload. If you have a good reason, why homonyms must be added to a checklist, it is recommended to add them manually. An example are homonyms, where a replacement name has not yet been published. Thus, the name Herpothallon hyposticticum was published twice ‒ once as a species assumed to be endemic to the Galapagos, then also for a species reported from Florida. The name that was published first, Herpothallon hyposticticum Bungartz & Elix from the Galapagos, has taxonomic priority. The name introduced for the species in Florida Herpothallon hyposticticum F. Seavey & J. Seavey is thus illegitimate. But as long as no replacement name has been published for the species from Florida, that taxon is still listed in the North American Checklist.

family override [max. 50 characters, title not displayed] = This field is not being displayed, but it can be used to organize a checklist using family names different from the Central Thesaurus. Thus, you may not accept the separation of Physciaceae and Caliciaceae, but prefer to treat both as subfamilies of one and the same superfamily. Or you may consider that the genus Ramalina should be listed in Ramalinaceae, not Bacidiaceae. This is possible by adding the preferred family name here, one that differs from the Central Thesaurus.

habitat [max. 500 characters, title not displayed] = This field was originally intended to display information about the habitat where a species is known to occur. For species included in checklists built for the Lichen Consortium the habitat field is sufficiently large to include the Esslinger categories whether a taxon is lichenized, a lichenicolous fungus, or a saprophytic or allied fungus [see ‘Assign Categories‘ below].

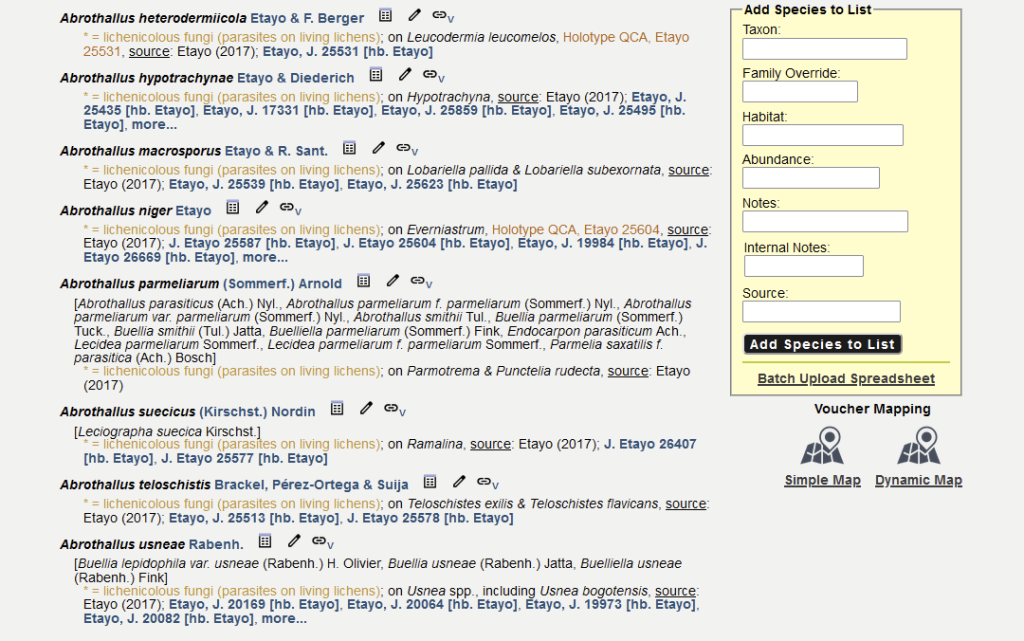

Some records of lichenicolous fungi included in the Ecuador Checklist:

The Esslinger category ‘lichenicolous’ has been added in color using html tags [see ‘Assign Categories‘], and the genus or species from which the lichenicolous fungus has been reported has been entered into the habitat field as well.

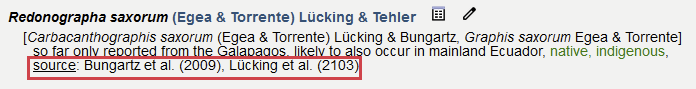

abundance [max. 50 characters, title not displayed] = This field is relatively small. For the Galapagos Checklist we have used this field to distinguish whether a taxon is considered endemic, native and/or indigenous to the archipelago [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

notes [max. 2,000 characters, title not displayed] = The notes field is sufficiently large to add detailed comments about a taxon, for example, if a taxon is considered problematic and why (it might have been only reported in the literature many years ago and no modern records exist, or the correct identification of specimens on which the report is based remains doubtful, etc.) [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

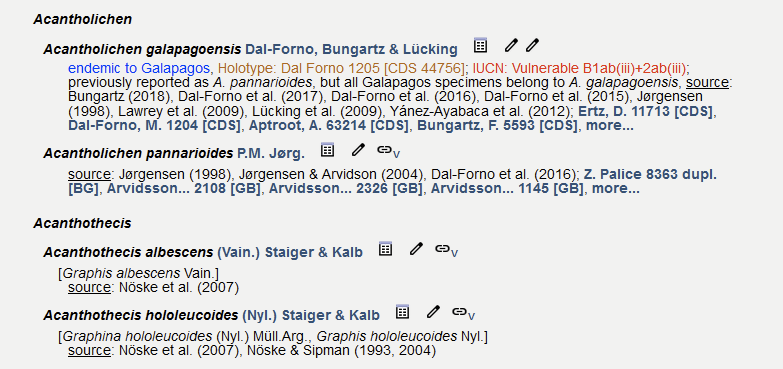

Screenshot from the Ecuador Checklist:

For Acantholichen galapagoensis the ‘abundance’ field contains the comment ‘endemic to Galapagos’, the ‘notes’ include a reference to the holotype and a comment that the species has been red-listed by the IUCN as vulnerable, as well as a comment that the species was previously erroneously reported from the Galapagos as A. pannarioides. The ‘source’ field lists relevant literature for which the complete list of references is included in a PDF that can be downloaded from the website. [different colors can be used with html tags, see ‘Assign Categories‘].

internal notes [max. 250 characters, this field is not displayed at all] = The field is not displayed and intended for comments that only checklist editors have access to. It is generally not very useful, because it is ‘invisible’ even to editors unless the data entry from is opened for each single taxon (or the whole checklist is downloaded as a spreadsheet).

Collaborating on a checklist draft, it is generally more convenient to temporarily use the other fields for adding ‘working notes’ (perhaps tagging them with a different color) and deleting them before publication, once the issue has been resolved.

source [max. 1,100 characters, title displayed as ‘source:’] = The source field is intended for literature citations. Although the field is quite large, it is not sufficient to add full reference citations here. A workaround is to use the general format how publications are typically cited in the scientific literature [e.g., Cole & Hawksworth (2001) or Suija et al. (2015)] and maintain a separate document with the full reference list, later to be added for download as a PDF, once the final list is being published [see the Ecuador Checklist as an example].

exercise #1:

Here an example of a CSV file with records in the format ready to be uploaded (a CSV file with UTF-8 character encoding):

Download the file, create a new, empty checklist and upload the data in batch:

This file will create a checklist providing some examples with the formatting, comments and colored categories used in the Ecuador Checklist (make sure to configure the display options to show the synonyms, notes & vouchers, taxon authors and organize the checklist alphabetically by genus, not family):

exercise #2:

The previous CSV file is a clean data set using the current taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus. Here a test file that that contains several problematic taxon names:

This file includes only two columns: sciname | source.

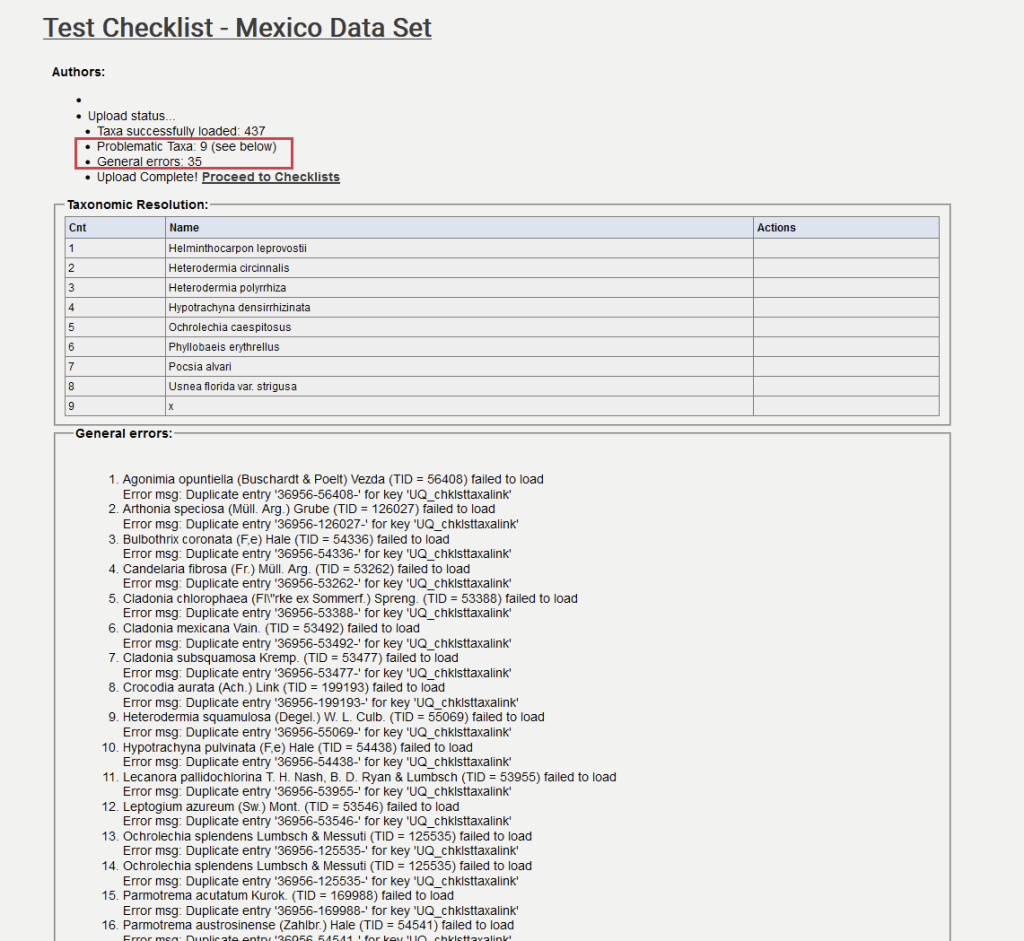

For the exercise, create a new checklist and upload the data from this CSV in batch. Here the result:

During upload, the authors were ignored. Nine taxon names could not be matched against the taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus. For example, line 477 of the CSV simply contains just an ‘x’ instead of a scientific name. That, of course, is not a name and the ‘x’ is thus ignored.

But eight other names could also not be matched. These names is erroneous:

- Helminthocarpon leprovostii (incorrect) – Helminthocarpon leprevostii (correct: the epithet is spelled with an ‘e’, not ‘o’)

- Heterodermia circinnalis (incorrect) – Heterodermia circinalis (correct: the epithet is spelled with only one ‘n’, not two ‘nn’)

- Heterodermia polyrrhiza (incorrect) – Heterodermia polyrhiza (correct: the epithet is spelled with only one ‘r’, not two ‘rr’)

- Hypotrachyna densirrhizinata (incorrect) – Hypotrachyna densirhizinata (correct: again the same error, one ‘r’, not two ‘rr’)

- Ochrolechia caespitosus (incorrect) – the name doesn’t exist

- Phyllobaeis erythrellus (incorrect) – Phyllobaeis erythrella (correct: the genus is feminine and the epithet thus ends with ‘-a’, not ‘-us’)

- Pocsia alvari (incorrect) – Pocsia alvaroi (correct: even though the taxon was originally published with the ‘alvari‘, this spelling is an orthographic error; the species was described in honor of Mexican botanist Álvaro Campus and the epithet must thus be spelled, ‘alvaroi‘.

- Usnea florida var. strigusa (incorrect) – Usnea florida var. strigosa (correct: the epithet is spelled with an ‘o’, not ‘u).

This list of problematic taxa that cannot be resolved, because of the incorrect spelling of the taxon names. The spelling errors must be corrected before these names can be uploaded again.

During upload some General Errors also occurred. That list is typically collapsed, but when expanded most of these errors are due to names repeated in the CSV file. These names are duplicates (Error message: ‘duplicate entry’). Basically, during upload the same names cannot be added twice.

However, there is a ‘catch’ with uploading duplicates; it is possible to create duplicates inadvertently by uploading both an accepted name and its synonym.

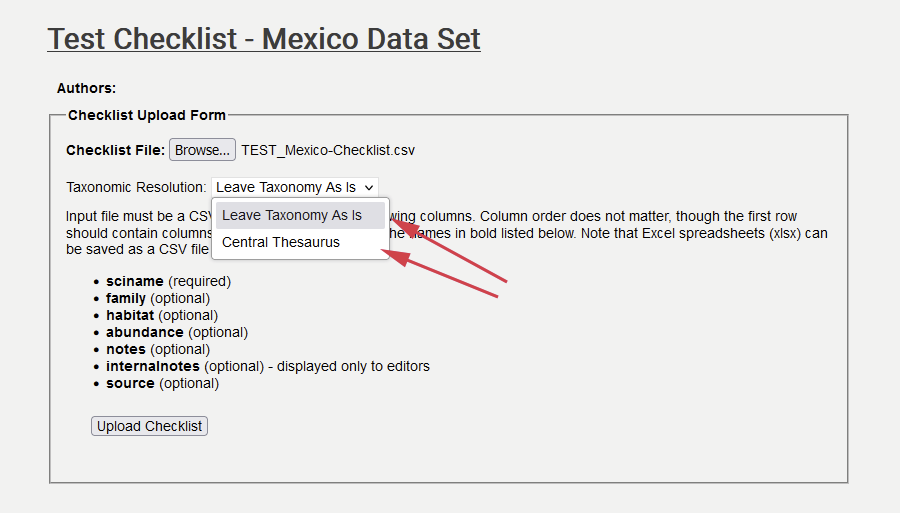

During batch-upload of a CSV two options are available:

Leave Taxonomy As Is = This option uploads the list of names ‘as is’, i.e., exactly as they appear in the CSV, ignoring whether some names are treated by the Central Thesaurus as ‘accepted’, others as ‘synonyms’.

This means, using this default option two names referring to the same taxon (e.g., Usnea longissima, and Dolichousnea longissima), will be uploaded, thus creating false duplicates. Therefore the option should only be used if authors deliberately prefer to ignore the taxonomy used by the Central Thesaurus.

Central Thesaurus = This option matches names included in the CSV against the taxonomy managed by the Central Thesaurus. For species that the Thesaurus treats as synonyms, only the accepted name is being uploaded (even if the original list contains only the name considered a synonym).

Be aware that adding only the ‘accepted names’ following the Central Thesaurus may in some instances result in names being added that a checklist author might not prefer. Thus, in the previous example, it is largely a matter of opinion whether Usnea longissima or Dolichousnea longissima is the preferred name for this taxon.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

3. Voucher Tool

All checklists ultimately refer back to reports of species from a particular country or region. Traditionally, most of these lists have been compiled based on reports in the literature. Literature reports, however, can be difficult to verify: Has the taxonomy changed? Can the reports be traced back to specimen records? Are identifications of these specimens correct?

Checklists built with Symbiota thus provide tools to built species lists by adding specimen records available in the Consortium. Such reference specimens are called vouchers. The idea is that not just any specimen record is added to a checklist, but only those taxa are added to a checklist, where voucher specimens have been reviewed and the identifications can be trusted.

Access the Voucher Tool with the ‘V’ button:

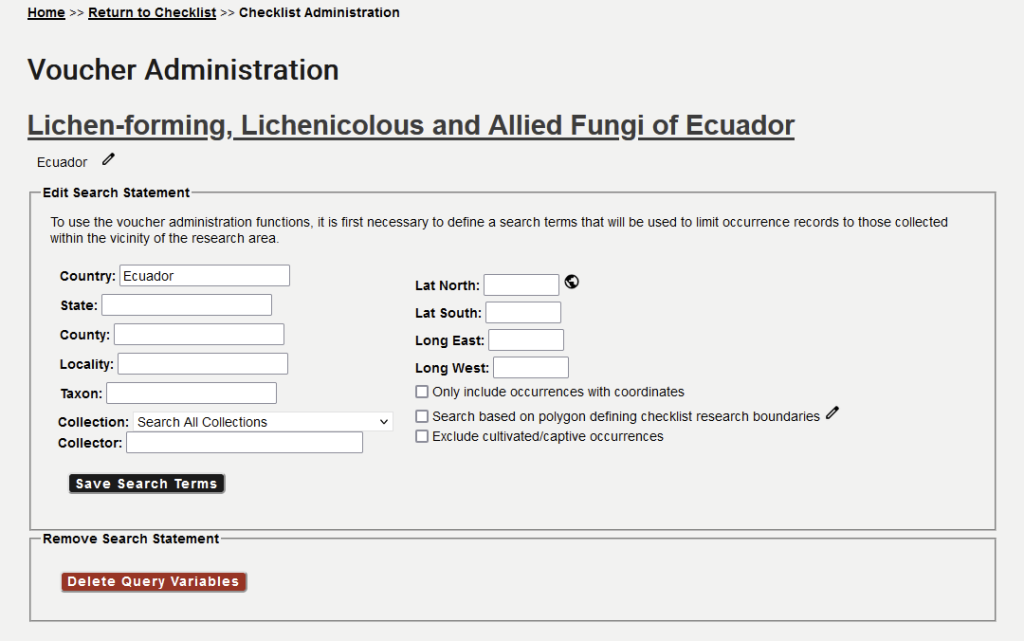

The first time the Voucher Tool is used, it is necessary to define a query, which specimens will be returned to be added to a checklist:

It is generally recommended to use fairly broad search parameters; in the example above the query will return all specimens from the country of Ecuador, from all collections in the Consortium.

It is possible to further narrow down these criteria, for example by returning only records from specific collections, or focusing on particular taxonomic groups, like families or genera. The query can also be restricted to return only records that have coordinates and will thus show up on a distribution map. A bounding box or a polygon that defines a specific area or geographic region can also be defined. [Unlike vascular plants lichens generally are not cultivated and that checkbox is thus irrelevant].

Narrowing down the parameters of this query can be useful to break down the workflow of selecting vouchers when the number of specimens returned may be overwhelming. Thus it is possible, for example, to first review only a particular taxonomic group from a region of interest. This can also be useful, when taxonomists with different expertise collaborate. One author might review all the Graphidaceae, while another one works on a different group. Since the query parameters cannot be saved individually per user, this requires some coordination if users work on a checklist concurrently.

3.1. verify IDs & select vouchers

The concept of using occurrence records from the Consortium as vouchers assumes that generally not just any record can be trusted to have been correctly identified. So, the exercise of adding vouchers to a checklist assumes that authors have had opportunity to review the material, or add only vouchers where they reasonably trust that the identification is accurate. Else, a comment should be added to the notes, why a doubtful or problematic record has been added [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

Once a query has been defined a tabbed view displays several lists:

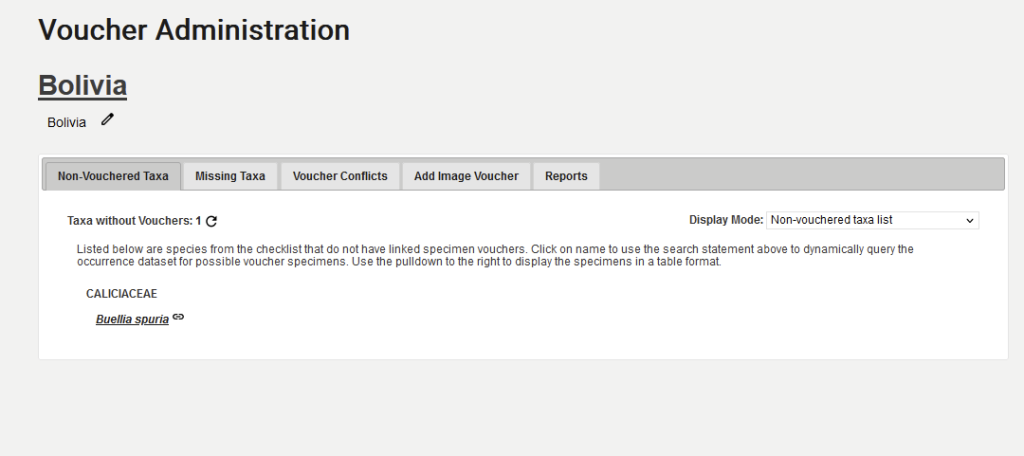

Non-Vouchered Taxa = When taxa have been manually added to a checklist or if a checklist has been uploaded in batch, none of these taxon names included in the newly built list are based on vouchers. The first tab thus presents a list of taxa for which no vouchers are available (yet). The chain icon runs a query where vouchers can be added, if occurrence records are available for that particular taxon.

Three display modes are available:

- ‘Non-Vouchered Taxa’ (the default) IMPORTANT – linking taxa manually using the ‘chain’ icon ignores the taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus; it is therefore best to avoid this default option

- ‘Occurrences for Non-Vouchered Taxa’ = a table view, a much more convenient mode to add vouchers. IMPORTANT – review the detailed specimen information carefully before adding vouchers [and best add vouchers only using the current taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus, see below].

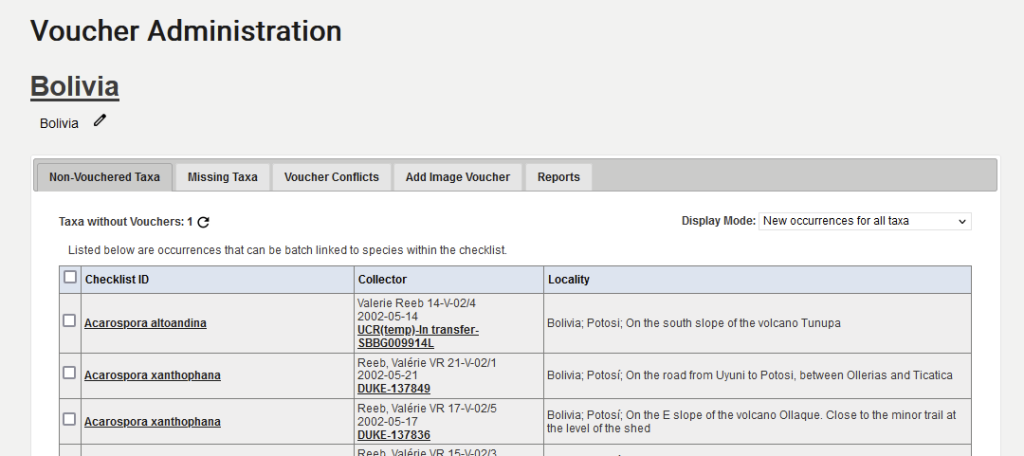

- ‘New Occurrences for All Taxa’ = a table of vouchers for taxa already included in the checklist, where additional vouchers may be added.

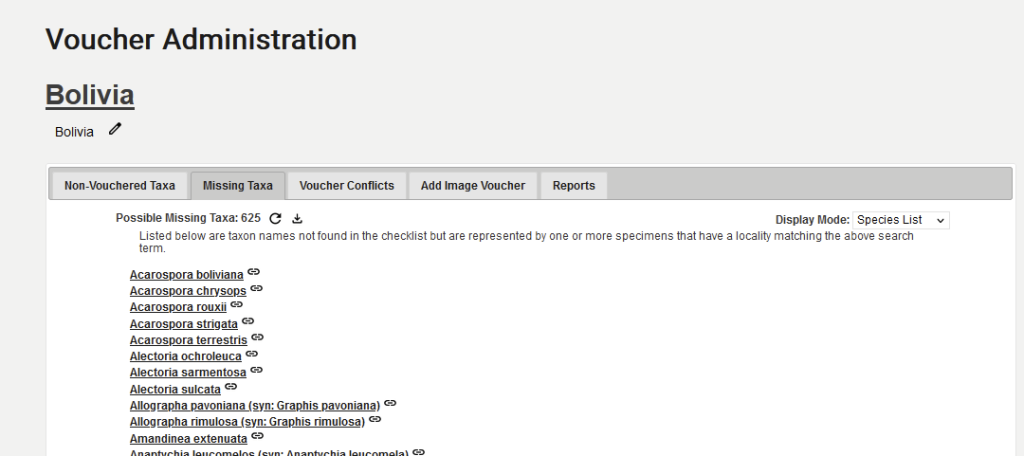

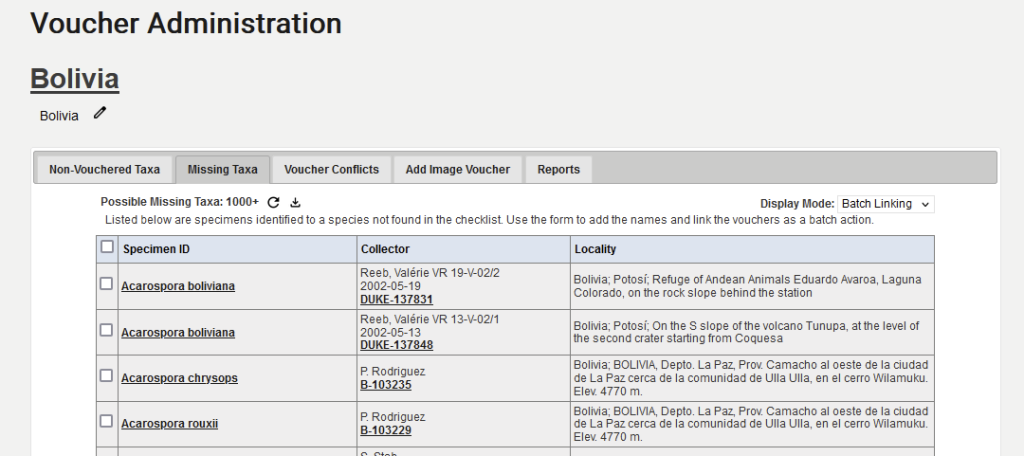

Missing Taxa = This tab presents a list of taxa for which occurrence records (= specimens) have be found [based on the search criteria of the query], but where these taxa are (still) not included in the checklist. Again, the chain icon will present a list of occurrence records that can be added individually.

Three display modes are available:

- ‘Species List’ (the default) IMPORTANT – linking taxa manually using the ‘chain’ icon ignores the taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus; it is therefore best to avoid this default option.

- ‘Batch Linking’ = a table view, that permits selecting only specific vouchers as trusted evidence that a taxon should be reported from the area. IMPORTANT – review the detailed specimen information carefully before adding vouchers [and best add vouchers only using the current taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus, see below].

- ‘Problem Taxa’ = a table of possible matches (based on the query), where the identification of occurrence records does not match any taxon in the taxonomic thesaurus [before re-linking these specimens to identifications not included in the taxonomic thesaurus, it is recommended to contact the Consortium administrator if taxon names need to be added, respectively the collections manager of a particular collection, if name records are erroneous and might need to be updated using the taxonomic name cleaner].

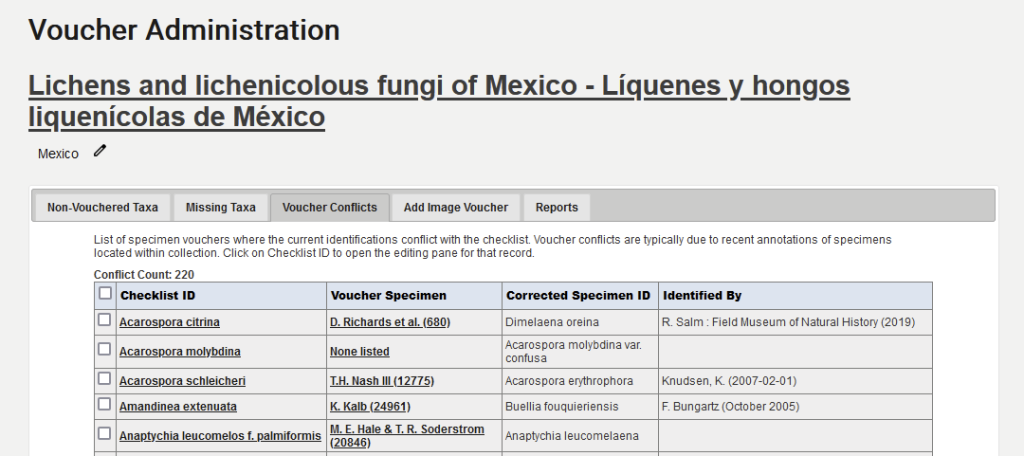

Voucher Conflicts = Conflicts arise when identifications of occurrence records change. This can happen for nomenclatural reasons, for example, when a species is placed into a new genus. But it can also happen, when a species previously accepted is reduced to synonmy. And it happens, when material is examined and the identification of a specimen is revised/corrected.

A simple change in the taxonomy (i.e., placing a species into a new genus) will not be flagged as a ‘voucher conflict’, but when the identification of a specimen changes and no longer matches the name in the checklist, these changes are listed here:

Add Image Voucher = For lichens it is not recommended using this tab. Reliable species identifications are not possible based on image records.

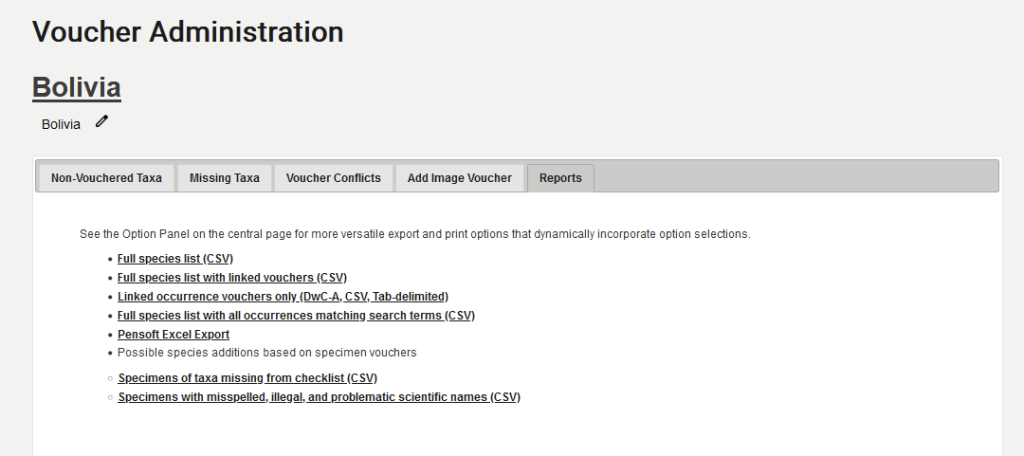

Reports = In addition to the general options to download a checklist as CSV, print the checklist in the browser or download it as a word document, the ‘reports’ tab adds more sophisticated download formats:

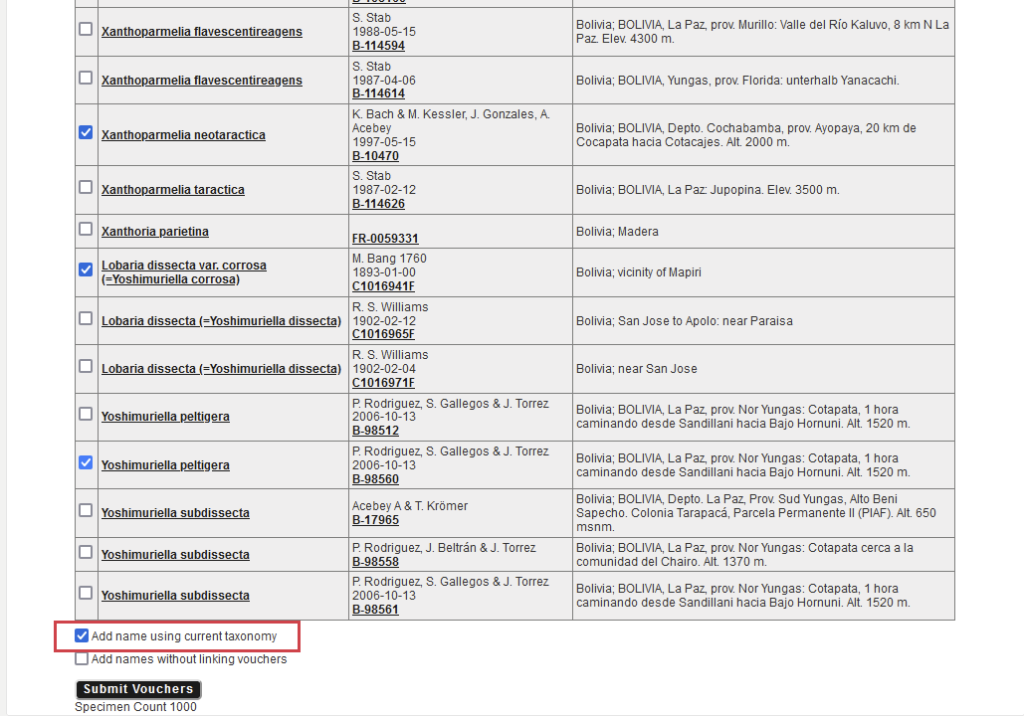

3.2. add using ‘current taxonomy’

As previously discussed, it is possible to built a checklist by manually adding taxa, even if the Central Thesaurus considers them to be synonyms. This results in a checklist where the the numbers in ‘original checklist’ view and ‘central thesaurus’ view don’t match. The differences can be quite striking, in the example below 3,139 vs. 2,840 species, which means that the ‘original checklist’ lists 299 species more than accepted by the Central Thesaurus:

When uploading a CSV spreadsheet in batch, it is possible to match the list of species included in the spreadsheet against the taxonomy of the Central Thesaurus. This option is also available, when adding records using the Voucher Tool. In the example below, the taxa will be added to the checklist of Bolivia based on the vouchers that have been checked, but instead of the current identification of the occurrence record (= specimen), records are added following the taxonomy employed by the Central Thesaurus.

Attention: It is important to note that Symbiota follows the DarwinCore using the Identification Qualifier to deal with identification uncertainty. Commonly used abbreviations like ‘cf.‘, ‘agg.‘, ‘s.str.‘, ‘s.l.‘ are currently not included in any of these list. When assessing whether a specific occurrence record (= specimen) should be added as voucher this information is, however, very relevant.

Thus, a specimen identification annotated as ‘cf.‘ (Latin for ‘confer’ = compare with…) must be considered uncertain and it makes a difference, whether a name has been used to refer to a species group (‘agg.’), in broadest terms (‘s.l.’) or in the strict sense (‘s.str.’). If taxa are added to a checklist based on vouchers for which their identity remains unresolved, it is recommended to add a comment to clarify, why these reports may be considered preliminary or even problematic [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

_______________________________________________________________________________________

4. Type Specimens

(species described from a country)

Taxa originally described from a particular country or region necessarily should be included in a checklist for that country or region. Taxonomic repositories like Index Fungorum or Mycobank include detailed information about type specimens. For newly described species registration is mandatory, therefore that information is typically available, but increasingly so also for species described long ago.

Working on the Checklist of Ecuador and the Checklist of Mexico, Paul Kirk from Index Fungorum kindly provided a spreadsheet with detailed information about type specimens for fungi described from these countries.

4.1. decide which are lichens/lichenicolous/allied fungi

Index Fungorum or Mycobank do not distinguish between different lifestyles or fungi, whether species are lichenized, lichenicolous or perhaps even fungi of uncertain status commonly studied by lichenologists. Some genera (e.g., Arthonia) include even lichenized, lichenicolous and non-lichenized species. Lists of type specimens obtained from these repositories typically need to be reviewed; species of non-lichenized mushrooms should not be included in a checklist of lichenized fungi, even if those were originally be describe from the country of interest.

Here the original list provided by Paul Kirk of species of Fungi described from Ecuador (i.e., where the type specimens were collected in that country):

Followed by a version of the same spreadsheet, where an additional column ‘Fungus’ has been inserted. Species that are lichenized, lichenicolous or allied fungi included in the Ecuador checklist are highlighted in green (#2), those not to be included are in yellow (#1):

For the ‘Cumulative Checklist for the Lichen-forming, Lichenicolous and Allied Fungi of the Continental United States and Canada‘ Ted Esslinger distinguishes three categories of fungi that are not lichenized in the strict sense:

* = lichenicolous fungi (parasites on living lichens)

+ = saprophytic fungi related to either lichens or lichenicolous fungi, on various substrates

# = various fungi of odd or uncertain status: e.g.: those which are questionably or weakly lichen-forming; or algicolous/saprophytic; or parasitic when young but saprophytic or lichen-forming when mature; or lichenicolous lichens

It is recommended that these categories also be used, when compiling similar lists for countries other than the United States [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

4.2. standardized formatting of type citations:

In the Index Fungorum spreadsheet column M includes ‘Typefication Details’ ‒ typically the acronym of the collection where the holotype has been deposited, followed by the collector and collector number, and, if available, the catalog number of the specimen. For some taxa this information may be incomplete, the location where the type material has been deposited may be unknown and possibly was not indicated when the taxon was described. For those records additional research may be necessary reviewing the protologue.

If a type specimen is available in a collection participating in the Consortium, it may be possible to update the ‘Typefication Details’ from that record. Thus, for Redonographa galapagoensis the spreadsheet simply cites ‘Holotype CDS 29421’, where CDS is the acronym of the herbarium at the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galapagos and 29421 the catalog number of the specimen, but the material was collected by Bungartz with collector number 5208, thus in the main Ecuador Checklist the type is listed as …

Holotype: Bungartz 5208 [CDS 29421]

using the following html code to apply the color tagging: <font color=c2660b>Holotype: Bungartz 5208 [CDS 29421]</font>

… whereas for the Galapagos Checklist the full collection information has been added:

Type: Ecuador. Galápagos: Isla Santiago, ca. 5 km inland from the E-coast; 0° 16′ S, 90° 37′ W; Bungartz 5208 (CDS 29421 ‒ holotype!); previously reported as Carbacanthographis saxiseda (Bungartz et al., 2010) but was found to represent an undescribed taxon (Lücking et al. 2013)

… again using the same html color tags [see ‘Assign Categories‘].

4.3. taxonomic aspects of citing type specimens

Taxonomy keeps changing. Types remain connected to the original name, the basionym ‒ even if that taxon is transferred into another genus (homotypic synonym) or if it is now considered synonymous with a different species (heterotypic synonym).

Thus, Allographa pedunculata was originally described from the Galapagos as Graphis pedunculata [homotypic synonyms]; the type specimen for both remains the same: Holotype: Bungartz 5701 [CDS 28799].

For heterotypic synonyms it is important to include a comment that the type cited strictly refers only to a particular taxon, which is now considered a synonym of the name included in the checklist.

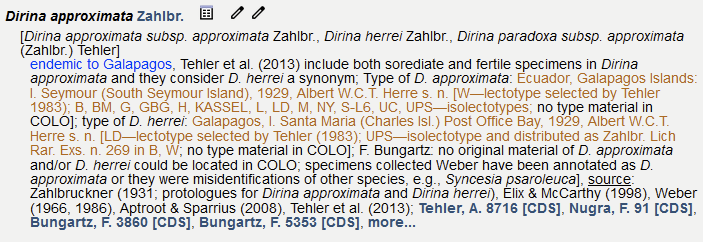

For example, Dirina approximata is the current name for a species endemic to the Galapagos. It was originally described from the Galapagos based on the following type:

Ecuador, Galapagos Islands: I. Seymour (South Seymour Island), 1929, Albert W.C.T. Herre s. n. [W—lectotype selected by Tehler 1983); B, BM, G, GBG, H, KASSEL, L, LD, M, NY, S-L6, UC, UPS—isolectotypes; no type material in COLO]

Tehler et al. (2013) suggest that Dirina herrei, also described from the Galapagos refers to the same species and thus must be considered a synonym. The type of D. herrei, however, is different:

Galapagos, I. Santa Maria (Charles Isl.) Post Office Bay, 1929, Albert W.C.T. Herre s. n. [LD—lectotype selected by Tehler (1983); UPS—isolectotype and distributed as Zahlbr. Lich Rar. Exs. n. 269 in B, W; no type material in COLO]

In the Checklist the species is listed as follows:

_______________________________________________________________________________________

5. Literature:

Traditionally, checklists are published on an extensive review of the taxa published in the scientific literature. Tools currently built into Symbiota are woefully inadequate. Presently, for each taxon record the ‘source’ (i.e., a simple text field) provides room for entering literature citations, and it is then also possible to include a reference list as a PDF.

It is anticipated that future versions will manage literature records in a more sophisticated way (the infrastructure for managing literature has already been built into the Symbiota backend database, but the user interface to cite and manage literature remains under development).

As long as more sophistic tools remain unavailable, one can use the following workaround:

5.1. review publications for records of species to be added to the checklist manually

‘Recent Literature Lichens is one of the most literature repositories for publications dealing with lichens. A quick search with the keyword ‘Mexico’ yields 646 records on publications dealing with lichens from Mexico.

These references obtained from RLL can be downloaded and the publications then need to be reviewed.

Records in RLL often include keywords, such as ‘New: Ramalina asahinae sp. nov.’, which suggests that this species was newly described in the following paper (obvious also from the title):

Culberson, W.L. & Culberson, C.F. (1976) Ramalina asahinae, a new boninic acid-producing species from Mexico. Journal of Japanese Botany 51: 374-376.

For many publications it is, however, not obvious, if a particular species has been cited from Mexico. For example, the ‘Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region‘ covers both parts of the US (Southern California and Arizona), but also parts of Mexico (Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sonora, parts of Sinaloa and Chihuahua). Thus, a reference like this one …

D. Ertz & Diederich, P. (2007) Plectocarpon. In: T. H. Nash, III, C. Gries & Bungartz, F.: Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region. Volume 3. Lichens Unlimited, Arizona State University, Tempe, pp. 402-403.

…needs to be reviewed in detail to assess, if species treated there were indeed reported from Mexico [in this case: both species of lichenicolous fungi in the genus Plectocarpon cited from the Sonoran Region are known only from California and have not been reported from Mexico].

This traditional work of reviewing publications for reports of species is cumbersome, but an important aspect of the research compiling checklists. Ideally, the evidence, why a taxon is reported from a region or country should be combined: both based on citing voucher specimens (as a record that can be verified) and citations in the scientific literature (to document what has previously been reported; ultimately many publications also include references to the specimens that document why a taxon has been reported in that publication).

Reviewing the list of publications downloaded from RLL, the following categories may be useful (we suggest highlighting the reference entries using the following colors):

Done = taxa cited in the literature have already been added to the checklist; literature has been cited both in the ‘notes’ and the publication has been added to the reference list

To Do = literature that still needs to be reviewed, which taxa have been cited

Problematic = doubtful records; the publication does not cite any specimen material, the literature record is old and it might not be clear what taxon these records specifically refer to ‒ if the record is added to the checklist it should be tagged as problematic or preliminary with a comment why this record remains doubtful [see ‘Assign Categories’]

[From Child Checklist = Records from a Child Checklist, to be included in the parent; this typicall happens automatically, the child feeding into the parent checklist; however, it is often necessary that there are no data discrepancies between parent and child checklist]

Duplicates = the same publication is listed twice; it only needs to be reviewed once and when compiling the final reference list, obviously only one of the duplicates should be included

Irrelevant = the publication deals with topics not relevant to biodiversity (e.g., physological studies on lichens; however: sometimes species may be reported for the first time from a country or region in a paper that does not mainly focus on biodiversity)

Unavailable = a copy of the publication could not be found (it is frequently difficult to find original literature; posting a message on the lichen listserv asking for help can be useful)

5.2. create a standardized reference list

Currently, tools that facilitate adding literature citations to a checklist are under development. This means that references can be added for each taxon using the ‘source’ field. Here, citations should be entered in the way they are commonly typically cited in the literature, e.g.:

A complete Reference List can be compiled separately; for consistency we suggest to use the following format:

How to cite …

… Journal References:

Ahti, T. (2000) Cladoniaceae. Flora Neotropica 78: 1-362.

Andersson, N.J.(1855) Om Galápagos Öarnes Vegetation. Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps Akademien Handl. 2: 61-256.

Aptroot, A. & Bungartz, F. (2007) The lichen genus Ramalina on the Galapagos. Lichenologist 39(6): 519-542.

Bungartz, F., Elix, J.A., Yánez-Ayabaca, A. & Archer, A.W. (2015) Endemism in the genus Pertusaria (Pertusariales, lichenized Ascomycota) from the Galapagos Islands. Telopea 18: 325-369 (http://dx.doi.org/10.7751/telopea8895).

Dal-Forno, M., Bungartz, F., Yánez-Ayabaca, A., Lücking, R. & Lawrey, J.D. (2017) High levels of endemism among Galapagos basidiolichens. Fungal Diversity 85(1): 45–73 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13225-017-0380-6 ).

… Scientific Proceedings:

Darbishire, O.V. (1935) The Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences, 1932. No. 23: The Roccellaceae with Notes on Specimens Collected During The Expedition of 1905-06 to the Galapagos Islands. Proceedings of the Californian Academy of Sciences, 4th Series, 21(23): 285-294.

… Online Resources:

Bungartz, F. (2018) Acantholichen galapagoensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T95836378A95838134 (http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T95836378A95838134.en); accessed 31 Oct 2018

Bungartz, F., Ziemmeck, F., Yánez Ayabaca, A., Nugra, F. & Aptroot, A. (2013d) CDF Checklist of Galapagos Lichenized Fungi. In: Bungartz, F., Herrera, H., Jaramillo, P., Tirado, N. Jiménez-Uzcátegui, H., Ruiz, D., Guézou, A. & Ziemmeck, F. (eds.) Charles Darwin Foundation Galapagos Species Checklist. Charles Darwin Foundation, Galapagos (http://checklists.datazone.darwinfoundation.org/true-fungi/lichens/); accessed 3 Dec 2013.

Kirk, P. (ed.) (2010) Index Fungorum. CABI Bioscience, CBS and Landcare Research (www.indexfungorum.org); accessed 25 Jan 2010.

… Complete Books:

Brodo, I.M., Duran Sharnoff, S., & S. Sharnoff (2001) Lichens of North America. Yale University Press, New Haven & London. 795 pp.

… Book Chapters:

Clerc, P. (2008) Usnea. In: T. Nash III, C. Gries & F. Bungartz (eds.) Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region, Vol. III. Arizona State University, Tempe, pp. 302-335.

Diederich, P. (1995) New or interesting lichenicolous fungi VI. Arthonia follmanniana, a new species from the Galapagos Islands. In: Daniels, F.J.A., Schultz, M. & Peine, J. (eds.) Flechten Follmann. Contributions to Lichenology in Honour of Gerhard Follmann. University of Cologne, Cologne, pp. 179-182.

Grube, M. (2007) Arthonia. In: Nash III, T.H., Gries, C. & Bungartz, F. (eds.) Lichen Flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region, Vol. III, Arizona State University, Tempe, pp. 39-61.

… Journal Sections:

Dodge, C.W. (1935) Lichenes. In: H.K. Svenson: Plants of the Astor Expedition, 1930 (Galápagos and Cocos Islands). American Journal of Botany 22(2): 221.

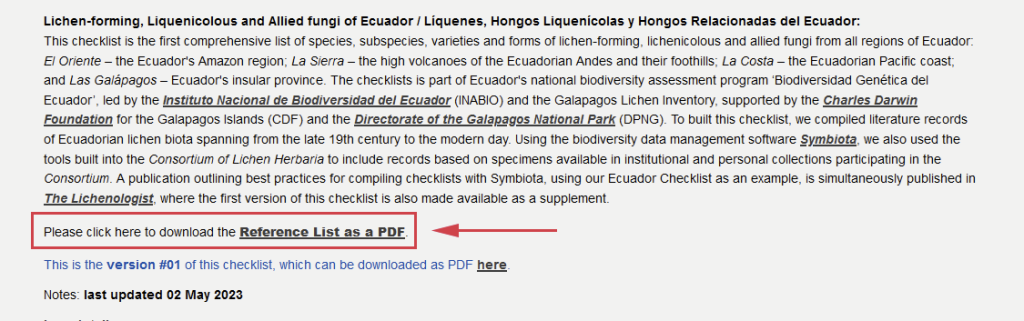

Download an example Reference List as a PDF from the Ecuador Checklist.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

6. Taxonomy Cleaning

As previously explained, there are many reasons why discrepancies between the Original Checklist and the Central Thesaurus result in different numbers of species displayed.

Here again the previous example where the Original Checklist lists 3,139 species but the Central Thesaurus reports only 2,840 species ‒ that difference of almost 300 taxa incluxded in the original checklist considered synonyms by the Central Thesaurus is enormous:

Most of these discrepancies happen, when species are added manually (for example based on the literature) not being aware that names in the meantime have changed. Only rarely do they reflect a different opinion, i.e., authors disagreeing with the Central Thesaurus suggesting that two species should be considered synonymous.

In most cases it is necessary to review and resolve these discrepancies.

6.1. how to resolve taxonomic discrepancies

Switching between ‘Original Checklist’ display and the ‘Central Thesaurus’ two versions of the same checklist can be downloaded as CSV, using the download button:

These two CSV files include also information irrelevant for the cleaning excercise. Copy the ScientificName colum from each download (‘Original Checklist’ and ‘Central Thesaurus’) side-byside into a new spreadsheet. The first colum now includes the 3,139 names from the ‘Original Checklist’, and the second column is a list of only 2,840 names from the ‘Central Thesaurus’.

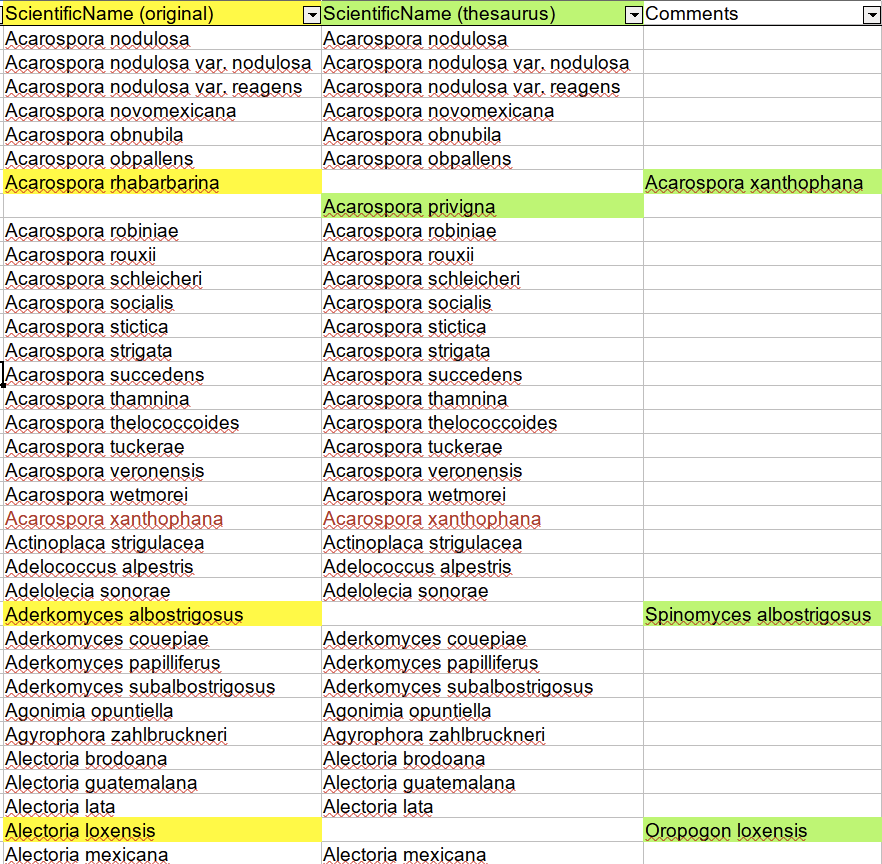

In a next step, you can review, which names occur both in the ‘Original Checklists’ and in the list displayed according to the ‘Central Thesaurus’. Names only in column 1 (original checklist), but absent from column 2 (central thesaurus) must be considered duplicates (below they are highlighted in yellow).

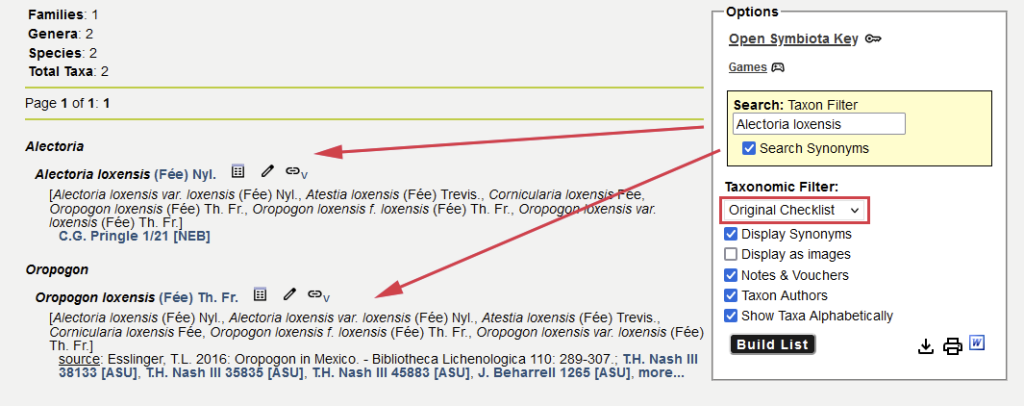

For example, Acarospora rhabarbarina is treated by the Central Thesaurus as a synonym of Acarospora xanthophana. The name Acarospora xanthophana therefore occurs in both the original checklist column and in the list displayed according to the Central Thesaurus.

In the Table below, we added a third column ‘Comments’ to include the accepted names for the synonyms duplicated in the original list:

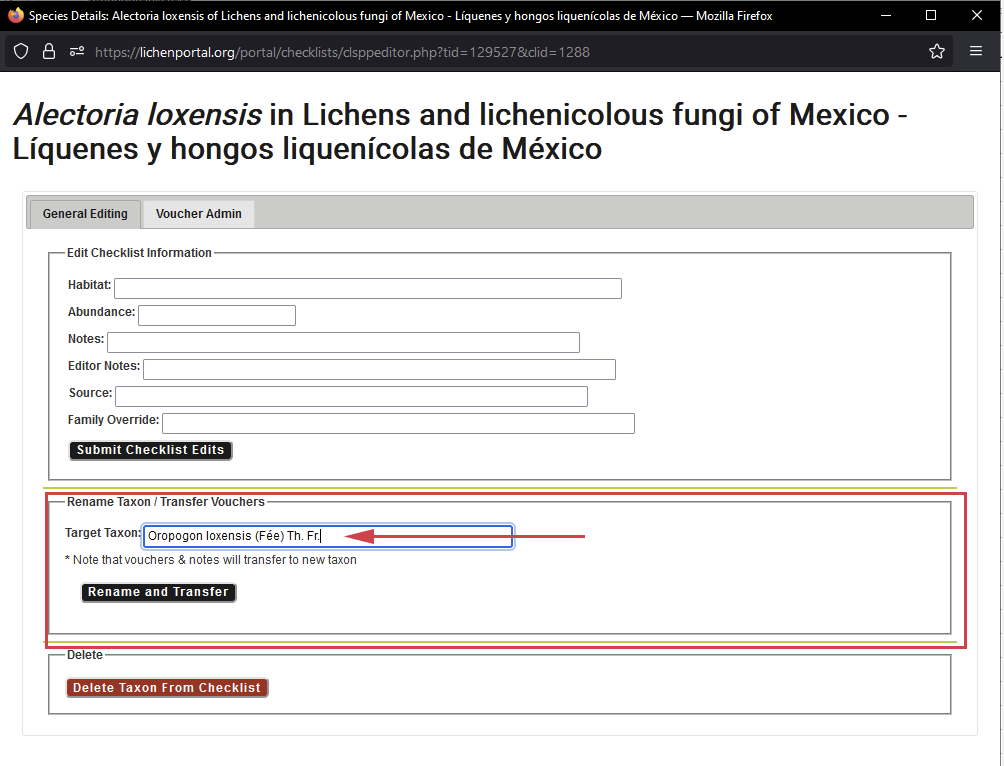

In the ‘Original Checklist’ Acarospora rhabarbarina is also listed as Acarospora xanthophana although the ‘Central Thesaurus’ treats A. rhabarbarina as a synonym of A. xanthophana. Aderkomyces albostrigosus should be listed only as Spinomyces albostrigosus. And Alectoria loxensis is a synonym of Oropogon loxensis:

Taxon names, the details, notes and vouchers can be transferred easily via the ‘Details’ pane (accessible via the pen icon), thus cleaning up the Original Checklist:

Cleaning up a large list with many discrepancies can be cumbersome. Thus, it is best review taxon names before adding them manually and for the CSV Batch Upload and Voucher Tool select the option to add names according to the Central Thesaurus.

6.2. review taxonomic repositories:

Some discrepancies can, however, not easily be avoided. The Taxonomic Thesaurus is not perfect. Names often need to be checked against Index Fungorum and/or Mycobank and even these repositories are far from complete. In many instances it is therfore necessary to consult the original literature and/or consult with experts.

Some discrepancies necessarily reflect different taxonomic opinion.

An example:

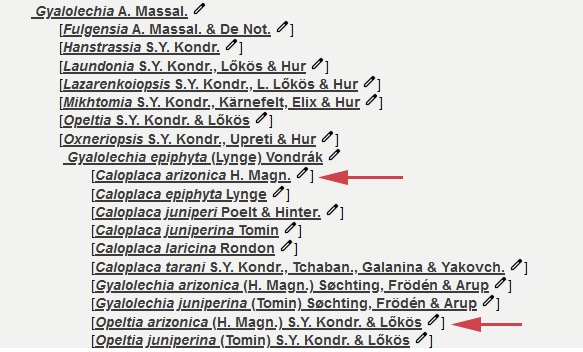

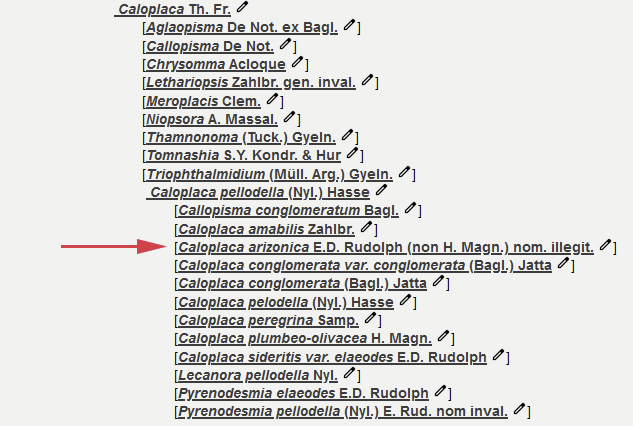

Caloplaca arizonica was described twice, first by Magnusson (1944), based on a type specimen collected by Dy Rietz in Arizona. Rudolph (1953) introduced the same name, based on a collection by Darrow.

Caloplaca arizonica H. Magn. is a valid name; it has priority. Caloplaca arizonica E.D. Rudolph is illegitimate, it was published later than Magnusson’s name.

Index Fungorum (Species Fungorum) suggests that should be considered a synonym of Opeltia arizonica (H. Magn.) S.Y. Kondr. & Lőkös, placed into that genus when Kondratyuk et al. (2017) proposed the new genus Opeltia.

However, Kondratyuk et al. (2017) were unaware that Vondrák et al. (2016) proposed to reduce Caloplaca arizonica H. Magn. to synonymy of Gyalolechia epiphyta (Lynge) Vondrák.

Unlike Species Fungorum, the Taxonomic Thesaurus of the Lichen Consortium follows the taxonomic concept proposed by Vondrák et al. (2016) and therefore treats Caloplaca arizonica H. Magn. and Opeltia arizonica (H. Magn.) S.Y. Kondr. & Lőkös as a synonym of Gyalolechia epiphyta (Lynge) Vondrák:

Now, what happened to the illigitimate homonym, Caloplaca arizonica E.D. Rudolph. It represents an entirely different species, based on a different type. It turns out that the type material available at ASU matches well with Caloplaca pellodella (Nyl.) Hasse, so the illegitimate name is treated by teh Taxonomic thesaurus as a synonym of that species:

_______________________________________________________________________________________

7. Assign Categories

Adding detailed information to a taxon in a checklist is a powerful way to clarify various aspects about the life form of the organism, their origin, and whether it is considered threatened. It can also be useful to add comments, why a record might only be included as ‘preliminary’ or why it is considered ‘problematic’. For species first described from a country it is useful to know where the type material is deposited.

Different fields are available to enter this information and html tags color can be used to make different aspect stand out. For the Ecuador Checklist we used the following color coded categories:

7.1. references to ‘type specimens’

For a more detailed discussion of how to include information on the Type Specimens see section on ‘Type Specimens‘ (enter the type info into the ‘Notes‘ field: problematic/preliminary, type comment, IUCN, then other notes):

Holotype: Dal Forno 1205 [CDS 44756]

Use the following html code for color tagging:

<font color=c2660b>Holotype: Dal Forno 1205 [CDS 44756]</font>

7.2. taxa included in the checklists that are ‘lichenicolous’ or ‘allied’ fungi

For the ‘Cumulative Checklist for the Lichen-forming, Lichenicolous and Allied Fungi of the Continental United States and Canada‘ Ted Esslinger distinguishes three categories of fungi that are not lichenized in the strict sense. It is recommended that these categories also be used, when compiling similar lists for countries other than the United States.

The Esslinger List uses symbols to tag the species names (* | + | #); for the Ecuador Checklist, we decided to use the full statement explaining these categories, using different colors (enter these tags into the ‘Habitat:‘ field):

lichenicolous fungi

* = lichenicolous fungi (parasites on living lichens)

Use the following html code:

<font color=#CC9933>* = lichenicolous fungi (parasites on living lichens)</font>

The substrate, i.e., the lichen that the lichenicolous fungus grows on might be added like this:

… on <i>Xanthoparmelia</i> …

… using the html tags to display the name in italics.

saprobes

+ = saprophytic fungi related to either lichens or lichenicolous fungi, on various substrates

Use the following html code:

<font color=#6e2c00 > + = saprophytic fungi related to either lichens or lichenicolous fungi, on various substrates</font>

allied fungi

# = various fungi of uncertain status: e.g.: those which are questionably or weakly lichen-forming; or algicolous/saprophytic; or parasitic when young but saprophytic or lichen-forming when mature; or lichenicolous lichens

Use the following html code:

<font color= #641e16> # = various fungi of uncertain status: e.g.: those which are questionably or weakly lichen-forming; or algicolous/saprophytic; or parasitic when young but saprophytic or lichen-forming when mature; or lichenicolous lichens</font>

7.3. endemic/native/indigenous

For island ecosystems, isolated mountain ranges, or otherwise unique regions, it is useful to denote, whether a species is considered ‘endemic‘, i.e., only found in that specific area. Species not native, but ‘introduced’ to an area where they did not naturally occur are are of conservation concern. They are considered ‘invasive‘, if they drastically alter an ecosystem, competing with and thus threatening native species.

For lichenized fungi any assessments whether species are endemic, native/indigenous, or introduced can be difficult, because their distribution remains less well known than for other groups of organisms. Adding these categories to a checklist, it is recommended to add also a comment into the ‘notes‘ field (for example, for which area a species is considered endemic, or whether a species is currently only known from a particular area, but likely more widely distributed). If necessary the terms below can be modified accordingly, e.g., ‘questionably endemic’ or ‘presumed to be introduced’ (use ‘Abundance‘ field):

native/indigenous

Use the following html code: <font color=green>native, indigenous</font>

Because endemic species are also native to the area from which they are known, the term ‘indigenous’ is occasionally used to emphasize that a species is native, but not endemic.

endemic to …

[if referring to a more confined area than the region covered by the checklist, specify what that category refers to, for example: endemic to the Galapagos]

Use the following html code: <font color=124dac>endemic to …</font>

Use this category with caution: Historic records that are not well documented should not be considered endemic. Species that have only recently been described and are likely to be found in a larger area, are also probably not endemic. Species for which the taxonomy has not been resolved should also not be treated as endemic.

introduced [invasive]

Use the following html code: <font color=red>introduced</font>

Use this category with caution: For most lichenicolous fungi, it appears very unlikely that a species would have been introduced to a particular habitat. Lichenized fungi are rarely used commercially (e.g., few reindeer lichens are sold as ornamentals, in India species of Parmotrema are used as spice, some species are used as dyes, in perfumes, or as medicinal natural remedies). Lichens cannot be cultivated either. Thus, there are no documented cases of deliberate, intentional introductions. It is of course possible that species were accidentally introduced, but even if this might be the case, there are no documented cases, where lichen species are assumed to significantly alter an ecosystem as invasives.

7.4. IUCN assessments

Refer to the Global IUCN Red-List for these assessments. It is useful not just to list the general assessment categories [data deficient (DD) | least concern (LC) | near threatened (NT) | vulnerable (VU) | endangered (EN) | critically endangered (CR) | extinct in the wild (EW) | extinct (E)], but also the criteria applied (refer to IUCN guidelines; enter into the ‘Notes‘ field: problematic/preliminary, type comment, IUCN, then other notes)]:

IUCN: Vulnerable B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii)

Use the following html code: <font color=cf2e2e>IUCN: Vulnerable B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii)</font>

[Note: for some countries regional assessments have been published; in these cases it is important to specify whether species are globally threatened or considered threatened only in the region of the checklist]

7.5. problematic & preliminary

(enter into the ‘Notes‘ field: problematic/preliminary, type comment, IUCN, then other notes):

The categories ‘problematic’ and ‘preliminary’ should not be used without further explaining why the records are considered that.

What’s the difference?

preliminary

Use the following html code: <font color=red>preliminary identification</font>, F. Bungartz: material needs verification

‘Peliminary‘ reports of some species may be based on records that have not yet been verified. These may be literature citations that are considered unreliable or identifications of voucher specimens that need to be reviewed. Clearly, not every voucher available in the Consortium should simply be added to a checklist. Only vouchers that can reasonably be trusted should be cited. But particularly for taxa that have already been cited in the literature, vouchers may still be included for which identifications are not necessarily considered final.

An example: Both Arthonia antillarum and A. parantillarum have been reported many times from the Neotropics. Nevertheless, the identity of the two species is not well resolved and at least in the Galapagos their secondary chemistry seems to differ from what has commonly been reported. Thus, the reports for Ecuador must be considered preliminary.

problematic

Use the following html code: <font color=red>problematic</font>

‘Problematic‘ reports of a taxon in a checklist are more difficult to assess. Frequently, names may have been cited in historic literature for which no modern record are available. These names are often unresolved, i.e., we do not know what particular taxon these names now refer to. But even names that were relatively recently published, may be considered problematic.

An example: For Ecuador, Werner & Follmann (2003) described Arthonia darbishirei, based on a specimen collected by Darbishire in 1872. The identy of that material could not be revised and the taxonomy of Arthonia is generally poorly resolved. Until type material has been studied, we consider the report problematic, even though the type collection is from Ecuador.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

8. Setting up the Header

Once the checklist is finalized, before making it publicly accessible, some final steps are still necessary: giving credit to the authors/contributors, adding an abstract explaining the scope of the checklist (geography/taxonomic group), adding a suggested citation, and configuring the default display options.

8.1. authors & institutional affiliations

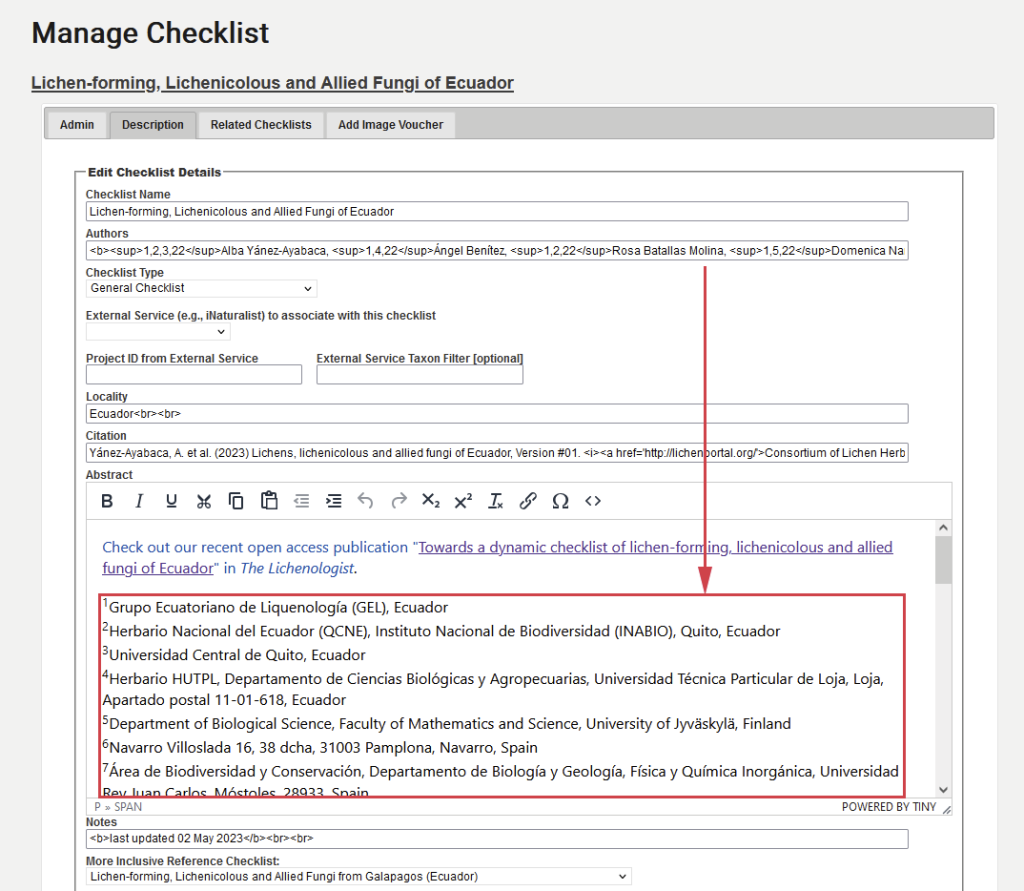

Checklists for entire countries are typically the result of a collaboration of many different authors. In the case of the Ecuador Checklist twenty-eight authors from multiple institutions collaborated on the list. Since there is no dedicated field for storing institutional affiliations, we decided to add this information to the abstract text field:

Only few Symbiota data entry fields have access to a dedicated text editor (like the ‘Abstract’ field), but generally most other fields support html tags. Thus, in the example above, displaying the numbers for the institutional affiliations of the checklist authors as superscript can be achieved using the <sup>…</sup> tags:

1,2,3,22Alba Yánez-Ayabaca, 1,4,22Ángel Benítez, 1…, 10Edward Erik Gilbert & *1,2,10,17,22Frank Bungartz

<sup>1,2,3,22</sup>Alba Yánez-Ayabaca, <sup>1,4,22</sup>Ángel Benítez, <sup>1</sup>…, <sup>10</sup>Edward Erik Gilbert & <sup>*1,2,10,17,22</sup>Frank Bungartz

8.2. useful html tags

Some basic html tags that are useful, when entering text [see also ‘Assign Categories‘]:

Most html tags require an opening tag and a closing tag, these don’t:

<br> = adds an extra line

<p> = adds an extra paragraph

These do:

<font color=”red”> … </font> = displays enclosed text in a different color, in this case red; html color codes, e.g., #AE3A94 can also be used.

<sup>…</sup> = displays enclosed text as superscript.

<sub>…</sub> = displays enclosed text as subscript.

<b>…</b> = displays enclosed text in bold.

<i>…</i> = displays enclosed text in italics.

Tags can also be combined, e.g.:

<b><i>…</b></i> = displays enclosed text in bold and italics.

More complicated is inserting links using html tags. For example to creat this link …

… you have to use the <a href>…</a> tags, like this:

<a href=’http://lichenportal.org/’>Consortium of Lichen Herbaria</a>

The first part of the tag <a href=‘http://lichenportal.org/’>…</a> refers to the internet address of the link, i.e., the URL that link points to. The second part is the title for the link to be displayed, <a href=’…’>Consortium of Lichen Herbaria</a>.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

9. Version History & Downloads

Traditional checklists are out-of-date quickly. Species previously not reported from a country or region might be newly discovered, other species are being described as new to science, the taxonomy of species changes, identifications of specimens turn out to be incorrect, previous reports are thus considered erroneous…

Traditional lists are thus often already out-of-date as soon as they get published.

Online checklists in the Consortium, however, can be easily updated. One particular useful tool is the ‘voucher conflicts‘ tab in the Voucher Tool. When identifications of specimens included as vouchers change, these discrepancies are displayed there. Discrepancies can thus be reviewed and vouchers linked to their new, correct identification, thus also updating checklists efficiently.

9.1. versions & version history

For small, regional research lists that are not widely shared, regularly updating a checklist is unproblematic and useful for keeping track of dynamically changing inventory data.

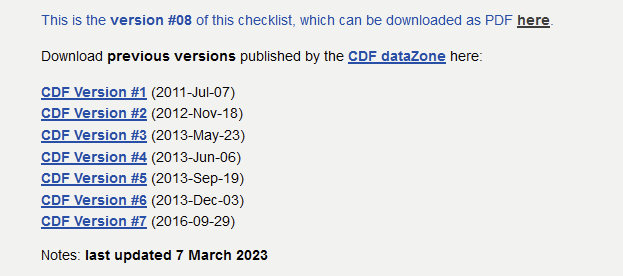

Establishing checklist to document biodiversity as a standardized list for a country, however, requires some stability. For the ‘North American Checklist‘ Ted Esslinger introduced the concept of checklists versions, publishing updates at semi-regular intervals. This not only offers a standard that conservation managers and researchers can adapt, version histories also document how knowledge about biodiversity changes over time.

There are no tools currently built into Symbiota to easily create different versions of a checklist. To create a new version, the raw data of an existing checklist must be downloaded and again uploaded using the batch upload. This creates a duplicate of an existing checklist ‒ although title, authors, abstract, default display configuration etc. still need to be copied over manually. Also, the new duplicate checklist does not include the vouchers; this nhas to be done by the Symbiota support in the database backend.

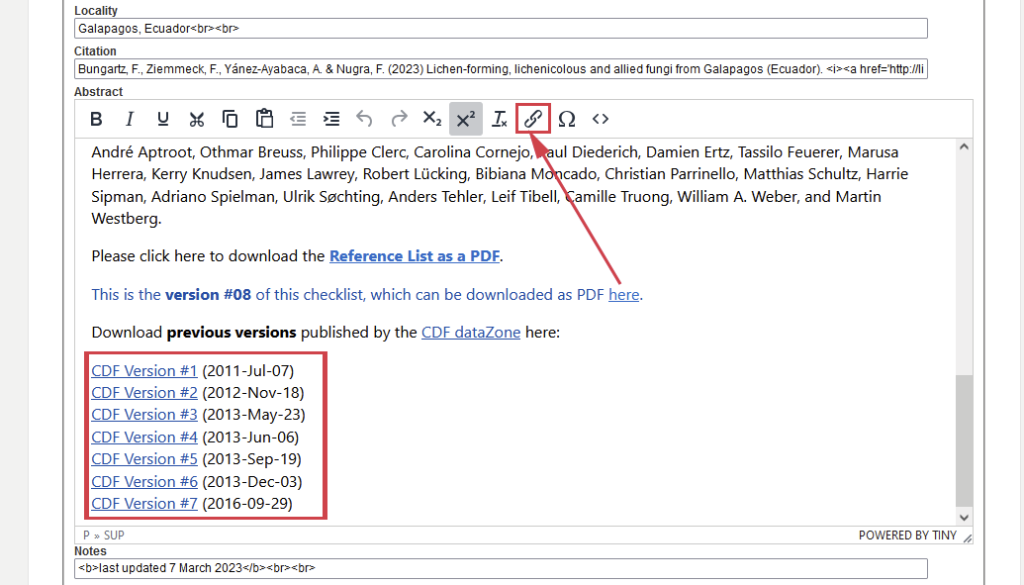

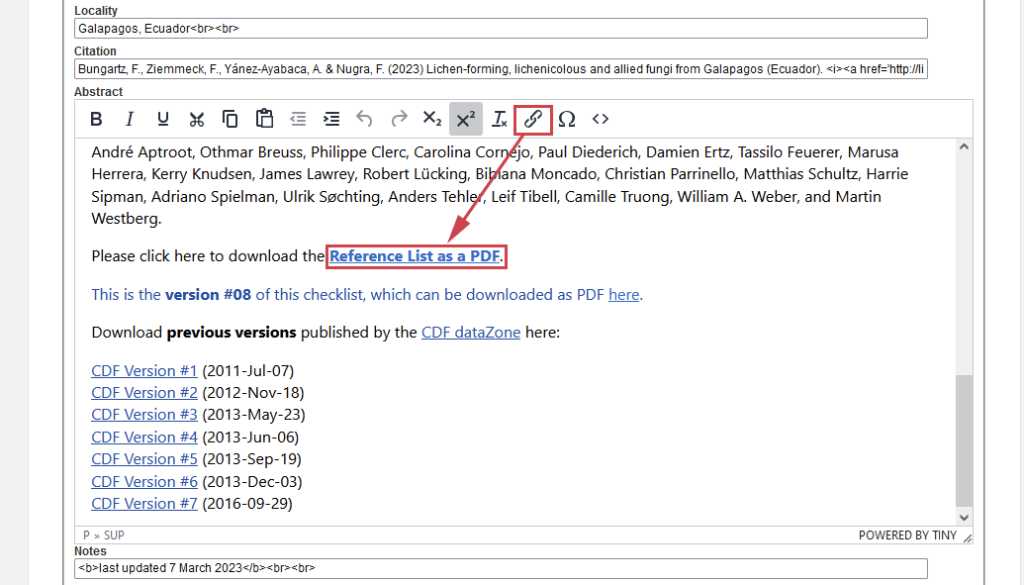

Previous versions of a checklist can be shared as PDF downloads from the main checklist (it is recommended also to include a note when the currentl list was last updated); here an example from the current Galapagos Checklist:

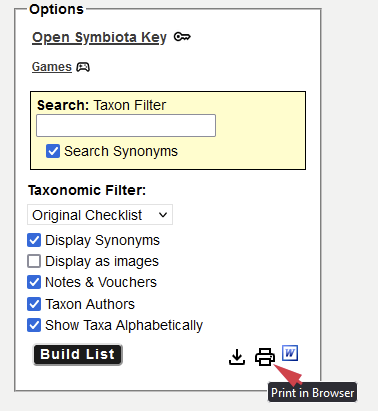

To quickly generate a PDF of the current version, the way the current checklist is displayed, use ‘print in browser’ and save the result as a PDF:

Once uploaded to the server, these PDFs than can be made available as downloads adding using the editor in the ‘abstract’ field (use the chain icon to add a link):

9.2. literature ‒ providing a download of the reference list

As previously discussed, Symbiota currently does not provide dedicated tools to add literature references to checklist records. The source field provides an option to add citations and an entire Reference List can then be made available for download as a PDF [see ‘create a standardized reference list‘ how to compile and format these lists].

That Referene List can then be made available for download, again using the abstract’ field (use the chain icon to add a link):

10. Publish the Checklist

10.1. workflow summary

- create a new, blank checklist & decide: hierarchical / non-hierarchical or a combination of the two

- [possibly add a rare species and/or species exclusion list]

- manually add taxa or upload a list in batch [make sure you check if taxomomy matches Central Thesaurus]

- use voucher tool to select occurrence records for which identifications can be trusted

- obtain a list of type specimens from your region and add these to the checklist

- review and add literature and create reference list

- review & clean taxonomy, resolve discrepancies, if necessary add taxa/synonymies to the Central Thesaurus [only possible with user rights that allow editing the Taxonomic Thesaurus; please send a list of names to be added to this email address].

- assign categories & add comments

- set up the header & add downloads (version history, reference list)

- configure display options & publish your list

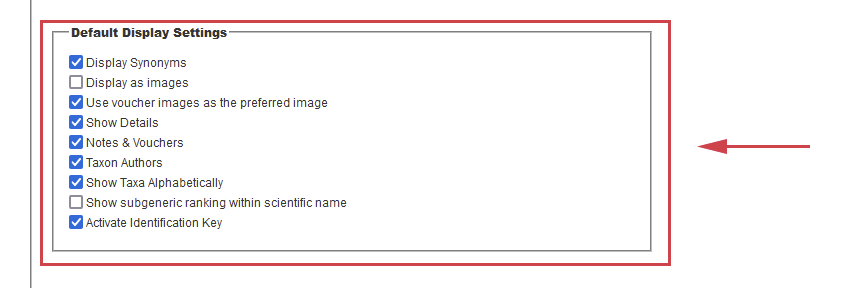

10.2. configure display options

Per default, new checklists are displayed as simple lists of taxon names grouped by family. This means no detailed information or vouchers is being displayed; to make sure this information is shown, it is recomended to use the follwing default display settings before switching the list from ‘private’ to ‘public’:

display synonyms = assures that synonyms according to the Central Thesaurus are shown

display as images = not recommended as this will reduce the list to display only images with taxon names as thier caption

use voucher inages as the preferred image = recommended; when a user changes the display manually to ‘images’, images from voucher specimens included in the checklist will be shown instead of random images pulled from the Consortium

show details = displays detailed information such as habitat, abundance, and source

notes & vouchers = displays the content from the notes field and the reference specimens selected as vouchers

taxon authors = displays the authors of the taxa included in a checklist [for fungi this is important, because nomenclature remains poorly resolved and especially when dealing with homonyms these can only be distinguished by their authors]

show taxa alphabetically = recommended; taxonomy of lichens is still in flux and it is generally more useful to display a checklist sorted by genus+specific epithet than by families first

show subgeneric ranking within scientific name = not recommended; subgeneric ranks have not widely been used in the taxonomy of lichenized fungi (the publication by Davydov et al. 2017 introducing subgenera of Umbilicaria is an exception).

activate identification key = taxa included in a checklist can be tagged using morphological, anatomical, ecological, and chemical charaters; this allows checklists to be used as identification keys; this option obviously only works well if all or at least the majority of taxa included in a checklist have been character coded.

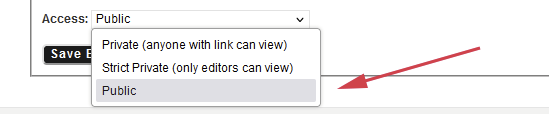

10.3. publish your list

While working on a Draft Checklist editors can decide if the URL should accessible to anyone with whom you share the link or only the editors with whom you collaborate.

With the first option ‘private (anyone with the link can view)’ you can share the URL with anyone who does not have editor rights. This may be useful, if you want to show potential collaborators what you are working on.

Choosing the second option ‘strictly private (only editors can view) means the URL is completely hidden and only users with editor rights to the checklist can view the list ‒ only when they are logged in with their user account.

Once you finished editing your list, changing the list to ‘public’ anyone can now view the new checklist:

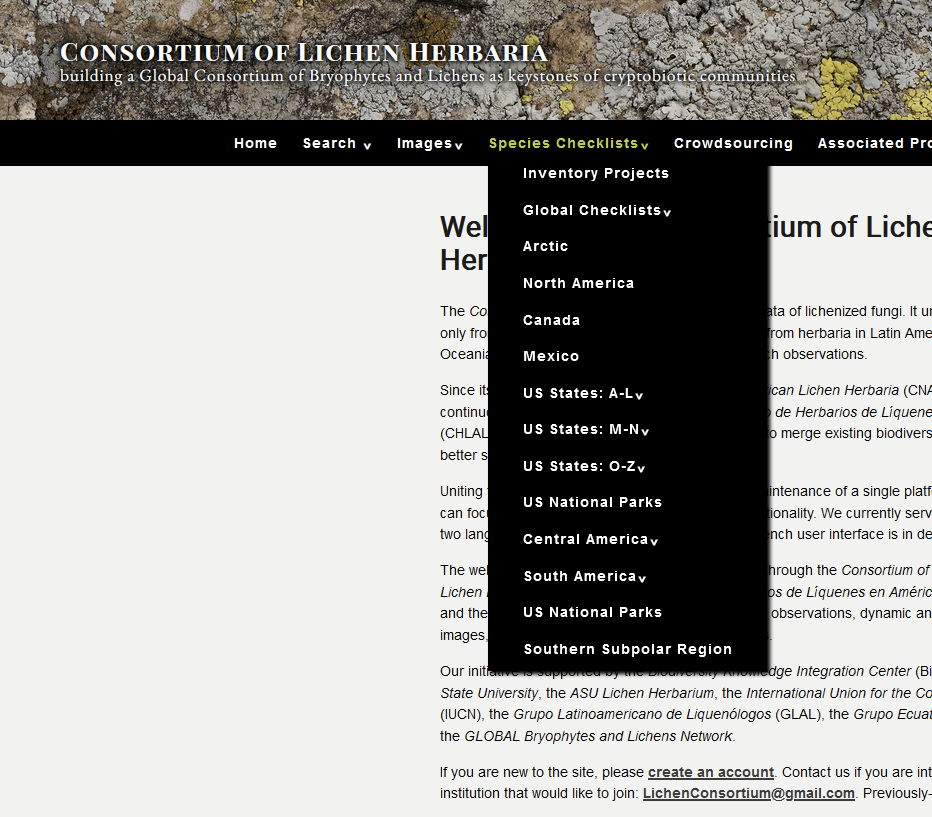

However, even though a new checklist is publicly available, it will not necessarily show up in the Checklist Menu of the Consortium:

The best way to make sure your checklist is accessible from that menu is to include the checklist as part of an inventory project; here for example the México Checklist Inventory (note that several of these lists are drafts, currently private, i.e., not yet published):